What is Sonic Narrative?

Curtis Roads Media Arts and Technology, University of California, Santa Barbara, United States

clangtint [at] gmail.com

http://www.curtisroads.net

Korean-translated by Youngmi Cho; assisted by Jinok Cho

Abstract

The active human mind imbues perceptual experiences with meaning: what we see and hear signifies or represents something. Even abstract sounds can articulate structural functions and evoke moods. This means that they can be used to design a narrative structure. A compelling sonic narrative is the backbone of an effective piece of music. This paper examines the important concepts of sonic narrative, including narrative function, sonic causality, nonlinear narrative, antinarrative strategies, narrative context, humor/irony/provocation, narrative repose, and hearing narrative structure.

Keywords

Narrative in computer music, Musical narrative, Structure of electroacoustic music.

음향적 서술이란 무엇인가?

커티스 로즈 미디어아트와 테크놀로지, 캘리포니아대학 산타바바라, 미국

clangtint [at] gmail.com

http://www.curtisroads.net

조영미 번역; 조진옥 교정 및 번역보조

초록

살아있는 인간의 정신은 지각적 경험에 의미를 부여한다: 우리가 보고 듣는 것이 무엇을 뜻하는지 어떠한 의미를 만들어준다는 것이다. 아무리 추상적인(비구체적인) 소리도 작품의 구조를 나타내고 어떤 분위기를 조성할 수 있다. 즉, 음악이 서술적 줄거리를 쓰는데 소리를 이용할 수 있다는 뜻이다. 설득력있는 음악적 서술 스토리는 음악작품의 효과에 근간이 된다. 이 글은 서술의 기능, 청각적 인과관계, 비순차적 서술, 반서술적 전략, 서술적 문맥, 유머/역설/도발, 서술적 휴식, 서술 구조 듣기를 포괄하여 음향적 서술의 중요한 개념들을 탐구한다.

주제어

컴퓨터음악의 서술, 음악적 서술, 전자음악의 구조.

Introduction

A composition can be likened to a being that is born out of nothing. Like all of us, it is a function of time. It grows and ambles, exploring a space of possibilities before it ultimately expires. This birth, development, and death make up a sonic narrative. Every level of structure, from sections to phrases, individual sounds, and even grain patterns follows its own narrative. Individual sounds come into being and then form complementary or opposing relationships with other sounds. These relationships evolve in many ways. Sounds clash, fuse, harmonize, or split into multiple parts. The relationship can break off suddenly or fizzle out slowly. Eventually, all the sounds expire, like characters in a sonic play. As Bernard observed (Gayou 2002):

If I have to define what you call the “Parmegiani sound,” it is a certain mobility, a certain color, a manner of beginning and ebbing away, making it living. Because I consider sound like a living being.

Or as Luc Ferrari (quoted in Caux 2002) said:

[My composition] Visage (1956) should be discussed in terms of cycles, rather than repetitions...I imagined the cycles as if they were individuals, living at different speeds. When they didn’t meet, they were independent. When they met...they were transformed by influence or by confrontation. In this way a sort of sentimental or narrative mechanism could be articulated.

A compelling sonic narrative is the backbone of an effective piece of music. This paper examines the important concepts of sonic narrative, including narrative function, sonic causality, nonlinear narrative, antinarrative strategies, narrative context, humor/irony/provocation, narrative repose, and hearing narrative structure. The text is adapted from chapter 10 of my book Composing Elec- tronic Music: A New Aesthetic (Roads 2015).

서론

작곡된 작품은 무에서 생겨나 실제하는 것에 비유할 수 있으며, 우리 모두와 마찬가지로, 이는 시간의 작용으로 존재한다. 이것은 자라나 서서히 전개하고, 음악이 궁극적으로 사라지기 전까지 많은 가능성의 공간들을 탐험하게 된다. 이 탄생과 발전, 결말에 이르는 과정은 하나의 음향 서술 이야기를 만든다. 악절과 악구, 개별 음들, 아주 작은 소리 입자를 포함한 모든 차원의 구성원들이 그 작품이 가지는 자체 서술 줄거리를 따라 구성된다. 각각의 소리가 태어나고, 이후 다른 소리와 보완적이거나 대립적인 관계가 형성된다. 이 관계들은 여러 방식으로 진화해 나간다. 각각의 소리들이 서로 충돌하거나 결합하고, 조화를 이루거나, 여러 조각으로 분열한다. 그 관계가 갑자기 중단되거나 서서히 소멸하기도 한다. 마침내, 이 모든 소리들은 하나의 소리 연극 속 등장인물들처럼 사라진다. 버나드 파르미지아니가 주시하였듯 (Gayou 2002):

당신이 “파르미지아니 소리”라 부르는 것을 내가 정의해야 한다면, 특정한 유동성과 특정한 색, 시작하고 사라지는 방식으로 그것을 살아있는 것으로 설명할 것이다. 왜냐하면 나는 소리를 생물과 같다고 여기기 때문이다.

혹은 루크 페라리(Caux 2002 에서 인용됨)가 말한 바에 따르면:

[나의 작품] 『얼굴 Visage』(1956)은 반복이라기보다 순환으로 보아야 한다... 나는 여러 순환들을 각각 서로 다른 속도로 개별적으로 움직이는 것으로 상상하였다. 서로 만나지 않으면 그들은 독립적으로 활동한다. 그들이 만나면... 영향력과 대립에 의하여 변형된다. 이러한 방식으로 감상적 혹은 서술적 매커니즘을 드러내게 된다.

설득력 있는 음악적 서술 스토리는 효과적인 음악 작품의 근간이 된다. 이 글은 서술의 기능과 청각적 인과성, 비순차적 서술, 반서술적 전략, 서술적 문맥, 유머/역설/도발, 서술적 휴식, 서술 구조 듣기를 포괄하여 음향적 서술의 중요한 개념들을 탐구한다. 본문은 나의 책 『전자 음악 작곡하기: 새로운 미학』(Roads 2015)의 10장에서 번안되었다.

Music is Representational

The active human mind imbues perceptual experiences with meaning: what we see and hear signifies or represents something. Thus sound, like other sensory stimuli, is representational. Even abstract sounds (i.e., music) can establish a mood or atmosphere within seconds, setting the stage for narrative. Consider the pensive tone of Daphne Oram’s Pulse Persephone (1965).

Sound 1.

Excerpt of Pulse Persephone (1965) by Daphne Oram.

Individual sounds also articulate structural functions. They signify beginnings, developments, transformations, and endings of larger structures. The fact sounds can articulate structural functions and evoke moods means that they can be used to design a narrative structure. As the theorist Jean-Jacques Nattiez (1990) observed:

For music to elicit narrative behavior, it need only fulfill two necessary and sufficient conditions: we must be given a minimum of two sounds of any kind, and these two sounds must be inscribed in a linear temporal dimension, so that a relationship will be established between the two objects. Why does this happen? Human beings are symbolic animals; con-fronted with a trace they will seek to interpret it to give it meaning.

I would go even further to say that a single sound can tell a narrative. A drone invites internal reflection and meditation. A doorbell alerts a household. An obnoxious noise provokes an immediate emotional reaction. Silence invites self reflection. An intense sustained sound commands attention (Figure 1, Sound 2).

Figure 1.

Setup for Xopher Davidson and Zbigniev Karkowski’s album Processor (2010). The Wavetek waveform generators (left) are controlled by a Comdyna GP6 analog computer (right). Photograph by Curtis Roads in Studio Varèse at UCSB.

Sound 2.

Excerpt of Process 5 (2010) by Xopher Davidson and Zbigniev Karkowski.

The conundrum of musical meaning has been analyzed at

length in the broad context of music cognition and music

semantics. Library shelves are filled with books on musical

meaning and the psychology of music.

As Elizabeth Hoffman (2012) observed, composers of electronic music often use recognizable or referential sound samples. Such works project listeners into encounters with places, people, and things–the stuff of narrative. The composer places these referential elements in a deliberate order. In works that use sampled sound to present a sound portrait, the connection to narrative discourse is direct. In many acousmatic pieces, we eavesdrop on people talking to themselves, to others, or to us. Taken to a dramatic extreme, some works tend towards the literal story lines of audio plays.

While the connection to narrative is obvious in these cases, what about narrative articulated by abstract sounds, that is, electronic sounds that are not sampled or not directly referential to events in the real world? First we must recognize that a distinction between abstract and referential sounds is clear only in extreme cases. An example of an abstract sound would be a sine tone lasting one second. An example of a referential sound would be a recording of a conversation. As we will see however, abstract sounds can serve structural functions in a composition. Thus they play a role in its narrative structure.

Many compositions propose no explicit social, cultural, or religious agenda. Like an abstract painting, they convey a pattern of rhythm, tone, and texture, i.e., what Denis Smalley (1986, 1997) called a spectromorphology. Spectromorphology describes patterns of sonic motion and growth according to acoustic properties. Abstract sound objects serve structural functions within these processes, such as beginning, transitional ascending element, climax, transitional descending element, pause (weak cadence), ending (strong cadence), juxtaposition, harmonizing element, contrasting element, and so on.

Sound 3.

Pictor alpha (2003) by Curtis Roads

Notice how the strong cadence of Pictor alpha is articulated simply by the repetition of a pulsar 6 dB greater than the previous pulsar, which clearly states: The End.

Inevitably, many sounds are charged with meaning beyond their purely spectromorphological function, for ex-ample, the spoken voice. We hear a spoken utterance not just as an abstract stream of phonemes but as human speech, full of expressive, linguistic, poetic, and conceptual ramifications. In music that relies on speech, the narrative often tends toward the literal, spilling outside the boundaries of “absolute” music, per se. An example is a scripted hörspeil or audio drama. Music based on spoken or sung text can recite a literal narrative, for example Ilhan Mimaroglu’s classic Prelude 12 for Magnetic tape (1967), featuring the evocative poetry by Orhan Veli Kanik.

Sound 4.

Excerpt of Prelude 12 for Magnetic tape (1967) by Ilhan Mimaroglu. (1)

We have our seas, full of sun.

We have our trees, full of leaves.

Morning til night, we go and go, back and forth.

Between our seas and our trees.

Full of nothingness.

Consider also soundscape compositions based on recordings of sonic environments. These run the gamut from pure audio documentaries to combinations of pure and processed recordings. Luc Ferrari’s Presque rien avec filles (1989) is an example of “cinema for the ear.” We recognize the sound sources so the signification is direct: we are transported to an artificial soundscape in the composer superimposes several recordings made at different times and places.

A primary strategy of self-described acousmatic music is precisely to play with reference. Acousmatic works en-gage in games of recognition, mimesis, and semantic allusion. The music of Natasha Barrett is a prime example.

The music of films often mirror the scripted plot and its associated emotions (fear, happiness, anger, amusement, grief, triumph, etc.) in more-or-less direct musical form. Of course, in more sophisticated productions, the music can function independently or even as ironic commentary, such as a light song dubbed over a tragic scene.

In contrast to these directly referential materials and strategies, representation is more abstract in much music (both instrumental and electronic). Consider a one-second sine tone at 261.62 Hz. It signifies “middle C” to someone with perfect pitch. It might also allude to the general con-text of electronic music, but other than this it represents a structural function that varies depending on the musical context in which it is heard. It might harmonize or clash with another sound, for example, or start or stop a phrase.

In works like my Now (2003), for example, a sonic narrative unfolds as a pattern of energetic flux in an abstract sonic realm. We hear a story of energy swells and collisions, of sonic coalescence, disintegration, mutation, granular agglomerations, and sudden transformation, told by means of spectromorphological processes.

Sound 5.

Now (2003) Curtis Roads

In such music, sounds articulate structural functions of the composition. Structural functions in traditional music begin with basic roles such as the articulation of scales, meters, tempi, keys, etc. and lead all the way up to the top layers of form: beginnings, endings, climaxes, developments, ritornelli, and so on. Analytical terms such as cadence, coda, and resolution directly imply scenarios. In a piece such as J. S. Bach’s Art of Fugue (1749), the narrative has been described as an exposition of “the whole art of Fugue and Counterpoint” as a process (Terry 1963). As Stockhausen (1972) observed:

Whereas it is true that traditionally in music, and in art in general, the context, or ideas and themes, were more or less descriptive, either psychologically descriptive of inter-human relationships, or descriptions of certain phenomena in the world, we now have a situation where the composition or decomposition of a sound, or the passing of a sound through several time layers may be the theme itself, granted that by theme we mean the behavior or life of the sound.

That music can teach us about processes leads to the ambiguity between “musical” and “extramusical” references. Music can articulate many types of processes; some grew out of musical tradition while others did not. Some com-posers of algorithmically composed music consider the narrative of their works (i.e., its meaning or what it articulates) to be the unfolding of a mathematical process. Se-rial music, for example, derives from set theory and modulo arithmetic, originally imported from mathematics. After decades of compositional practice, are these still “extramusical” references? The distinction is not clear.

음악은 상징적이다

살아있는 인간의 정신은 지각적 경험에 의미를 부여한다: 우리가 보고 듣는 것이 무엇을 뜻하는지 어떠한 의미를 만들어준다는 것이다. 그래서 다른 감각 자극과 같이 소리가 구체적인 표현을 하는 것이다. 추상적인 소리(예를 들어 음악)도 수 초 내에 어떤 기분이나 분위기를 만들고 서술을 위한 공간을 마련해 낼 수 있다. 다프네 오람의 『펄스 페르세포네』(1965)의 수심어린 음조를 생각해보라.

음악 1.

다프네 오람의 『펄스 페르세포네』(1965) 발췌분.

각각의 개별 소리들은 구조적인 기능도 명시한다. 그 소리들은 상대적으로 큰 구조의 시작과 전개, 변형, 결말을 표현한다. 소리가 구조적 기능을 보여주고 분위기를 불러일으킬 수 있다는 사실은 이들이 서술적 구조를 설계하는 데 사용될 수 있다는 의미이다. 이론가 장 자크 나티에(Nattiez 1990)가 보여주었듯:

음악이 서술적 작용을 하려면, 오직 두 개의 필요충분조건만 갖추면 된다: 최소한 두 가지 서로 다른 종류의 소리가 주어져야 하고, 이 두 소리는 순차적으로 다른 시간에 나타나야 하며, 그에 따라 두 소리 대상 사이에 관계가 성립하게 된다. 왜 이런 일이 일어나는가? 인간이란 존재는 그들이 쫓고자 하는 것의 흔적만 발견해도 그것에 의미를 부여하는 상징적인 동물이기 때문이다.

나는 심지어 더 나아가 단 하나의 소리로도 서술이 가능하다는 주장을 하고자 한다. 하나의 지속음drone은 우리를 내적 반영과 명상의 시간으로 초대한다. 초인종은 온 집안밖을 환기시킨다. 고약한 소음은 즉각적인 감정 반응을 불러일으킨다. 정적은 자기 성찰을 요청한다. 지독하게 계속되는 소리는 주의를 끌게 된다 (그림1, 음악 2).

그림 1.

소퍼 데이비드손과 즈비그니프 카르코브스키의 앨범 『프로세서』(2010). 웨이브텍 파형 발생기(좌)가 콤다이나 지피6 아날로그 컴퓨터(우)로 제어된다. 캘리포니아대학 산타바바라 바레즈 스튜디오에서 커티스 로즈가 찍은 사진.

그림 1.

소퍼 데이비드손과 즈비그니프 카르코브스키의 앨범 『프로세서』(2010). 웨이브텍 파형 발생기(좌)가 콤다이나 지피6 아날로그 컴퓨터(우)로 제어된다. 캘리포니아대학 산타바바라 바레즈 스튜디오에서 커티스 로즈가 찍은 사진.

음악 2.

소퍼 데이비드손과 즈비그니프 카르코브스키의 앨범 『프로세스 5』(2010)의 발췌분.

음악이 의미하는 바가 무엇인지의 수수께끼는 음악 인지학과 음악 의미론의 견지에서 폭넓게 그리고 상세히 분석되어 왔다. 도서관 서가는 음악적 의미론과 음악 심리학에 대한 책들로 가득 차 있다.

엘리자베스 호프만(Hoffman 2012)이 말하였듯, 전자음악 작곡가들은 종종 식별할 수 있거나 ‘특정 관련성이 있는’ 소리 샘플을 사용한다. 이렇게 만들어진 작품은 청자로 하여금 -서술 거리가 되는- 어떤 장소나 사람, 상황에 맞닥뜨리도록 만든다. 작곡가는 이 관련성 있는 요소들을 의도한 순서에 따라 배치한다. 샘플된 소리로 청각적 묘사를 실현한 작품에서는 직접적으로 서술 이야기에 연결된다. 우리는 여러 음향음악acousmatic 작품을 통해 사람들이 그들 자신에게나 타인에게, 혹은 우리에게 하는 이야기를 엿듯게 된다. 극단적인 예를 들자면, 어떤 음악작품들은 마치 글을 읽어주는 책처럼 문학의 스토리 라인을 따라 듣는 것 같은 인상을 주기도 한다.

위의 경우는 서술적 이야기로의 연결이 명확하지만, ‘추상적 소리abstract sounds’, 즉 실제 주변의 소리를 그대로 녹음한 것이 아니거나 무엇을 추정할 만한 소리가 아닌 전자 음향으로 그려지는 서술의 경우는 어떠할까? 첫째 우리는 추상적 소리와 추정 가능한 소리 사이의 구별은 오로지 극단적인 경우에만 명확히 할 수 있다는 것을 알아야 한다. 추상적 소리의 한 예로 1초 간 울리는 정현파음sine tone을 들겠다. 추정가능한 소리는 어떤 대화를 녹음한 것으로 예를 든다. 앞으로 더 언급하겠지만, 추상적 소리는 음악 작품에서 구조적인 기능을 할 수 있다. 따라서 서술적인 구조를 형성하는 역할을 하게 된다.

많은 작곡 작품들이 사회적, 문화적, 종교적 의도를 제시하지 않는다. 추상화에서처럼, 그들은 리듬이나 음, 성부조직의 형태 등 데니스 스말리(Smalley 1986, 1997)가 ‘음향형태분석학spectromorphology’이라 부른 것을 전달할 뿐이다. 음향형태분석학은 음향학적 특성에 따른 소리의 움직임과 성장의 형태를 분석한 스펙트럼을 시각적으로 보여주는 학문이다. 추상적 소리 개체는 구체적으로 열거하여, 도입, 점차 상승하는 요소, 절정, 점차 하향하는 요소, 중단(약한 종지), 결말(강한 종지), 병치, 조화하는 요소, 대조하는 요소 등과 같은 형태로 구조적인 기능을 담당한다.

음악 3.

커티스 로즈의 『화가자리 알파』(2003)

『화가자리 알파』의 강한 종지가 단순히 이전보다 6데시벨 더 큰 맥동 소리pulsar의 반복으로 확실한 결말을 이끌어낸 결과임을 주목하라.

불가피하게도, 많은 소리들이 대화 소리처럼 순수한 음향형태분석학적 기능 이외의 의미와 관련되게 된다. 우리는 대화 속 줄거리를 단순한 음소의 추상적 흐름이 아닌, 의미심장한, 언어로 이루어진, 시적이고, 개념적 파장이 충만한 인간의 언어로 받아들인다. 언어를 사용하는 음악에서, 서술성은 종종 그 자체로 문자적 성향을 띄며 “절대” 음악의 경계 밖으로 내몰린다. 그 예로 대본을 읽는 ‘라디오극hörspeil’이나 오디오북이 있다. 말이나 노래 가사가 있는 음악은 문자적으로 서술을 읊게 되는데, 그 예로 오르한 벨리 카니크의 연상적 시를 필두로 한 일란 미마로글루의 고전적 작품 『자기테이프magnetic tape를 위한 전주곡 12』(1967)가 있다.

음악 4.

일란 미마로글루의 『자기테이프magnetic tape를 위한 전주곡 12』(1967) 발췌본 (1)

우리는 우리의 바다가 있다, 햇빛이 가득 찬.

우리는 우리의 나무가 있다, 풀잎이 가득 찬.

아침부터 밤까지, 우리는 가고 또 간다, 여기저기로.

우리의 바다와 나무 사이로.

무의미로 가득 찬.

주변 환경의 소리 녹음에 기반한 소리환경soundscape 작품도 고려해보라. 이들은 녹음된 그대로의 청각 기록물부터 순수 녹음 자료와 처리 변환된 자료의 조합까지 온갖 범위에 이른다. 루크 페라리의 『소녀와 거의 아무것도』(1989)는 “귀로 듣는 영화”의 예이다. 우리는 소리의 출처를 알 수 있고, 그래서 그 의미를 즉각 알아차린다: 우리는 작곡가가 여러 다른 시간과 장소인 듯 꾸며놓은 녹음 기록을 통해 가상의 소리환경 세계로 여행 다니게 된다.

자체 묘사적 음향 음악의 주요 전략은 정확히 추정 가능한 대상이 있도록 만드는 것이다. 음향 음악은 인식과 모사, 의미 암시가 작용할 수 있는 장으로 펼쳐지게 된다. 나타샤 바렛의 음악이 그 주요한 예이다.

영화 음악은 종종 대본 줄거리를 따라 그와 연관된 감정(두려움, 행복, 분노, 즐거움, 슬픔, 승리감 등)을 반영하는 다소 서술에 직접적인 음악 형식을 사용한다. 물론, 보다 세심한 영화 제작 과정에서는, 음악은 독립적으로, 혹은 비극적 장면에 깔리는 경쾌한 노래처럼 역설적으로도 기능할 수 있다.

이렇게 직접적으로 추정되는 재료와 전략에 대비하여, 많은 음악(기악음악과 전자음악 둘 다)에서 나타나는 묘사는 보다 추상적이다. 1초 간의 261. 62헤르츠 정현파음을 들어 보라. 절대음감을 가진 누군가에게는 “가온 도”를 의미한다. 일반적인 전자 음악의 이야기로 비칠 수 있겠지만, 어떻게 듣느냐에 따라 이와는 달리 다각화된 구조적 기능을 할 수도 있다. 악구를 시작하거나 중단하듯 다른 소리와 어울리거나 대립할 지도 모른다.

저자의 『지금Now』(2003)과 같은 작품을 예로 들면, 청각적 서술 이야기가 추상적인 음향 세계에서 끊임없이 변화하며 영향력있는 형태로 펼쳐진다. 음향형태분석학으로 설명되는 소리의 융합과 분열, 변질, 미세한 것들이 한 덩어리로 뭉쳐졌다가 갑작스럽게 변신하는 과정을 통해, 스토리를 들으며 벅차오르거나 상충하는 에너지를 느낀다.

음악 5.

커티스 로즈의 『지금Now』 (2003)

이러한 음악에서, 소리는 작품의 구조적 기능을 보여준다. 전통 음악에서 구조적 기능은 음계와 박자, 빠르기, 조성 등을 명시하는 기본적인 역할로 시작해서, 도입, 결말, 절정, 발전, 반복재현 등 형식의 상위층까지 모든 방식을 이끌어 낸다. 종지와 코다, 해결 같은 분석 용어가 시나리오 줄거리를 직접적으로 시사한다. 바흐의 『푸가의 기법』(1749)과 같은 작품에서, 서술적 이야기는 “총체적인 푸가 기법과 대위법의 예술”의 과정을 전시하고 있다 (Terry 1963). 스톡하우젠(Stockhausen 1972)이 주목하였듯:

전통적으로 음악에서, 그리고 일반적인 미술에서, 맥락이나 아이디어, 혹은 주제가 인간의 내면 관계의 심리나 실상의 현상을 묘사한 것을 비롯하여, 다소간 묘사적인, 현재 우리가 의미하는 일상적인 소리의 소재라 할지라도, 여러 시간차에 근거한 소리의 구성과 해체, 소멸이 그 자체로 주제가 될 수 있는 상황에 처하게 된다.

이러한 음악은 우리에게 “음악적인” 그리고 “음악외적인” 대상의 차이를 모호하게 만드는 과정에 대해 알려 준다. 음악은 여러 종류의 과정을 보여줄 수 있다: 어떤 것은 음악적 전통에서 나왔지만 어떤 다른 것은 그렇지 않다. 알고리듬으로 음악을 만드는 어떤 작곡가는 수학적 과정을 펼쳐내며 그들 작품의 서술성(예를 들어, 그 의미나 그가 제시하는 것)을 고려한다. 예를 들어, 음렬 음악은 원천적으로 수학에서 도입한 집합론set theory과 모듈 산술에서 유래하였다. 수십년의 작업을 실행한 후라면, “음악외적” 추정이 가능하게 될까? 구별해내기 어려울 것이다.

Abstract Sonic Narrative

What is narrative? In a general sense, it is a story that the human brain constructs out of our experience of the world, by anticipating the future and relating current perceptions to the past. We are constantly building stories out of sensory experiences:

I am sitting. The walls are wooden. I see a red and white checkered pattern. I see green colors. I hear broadband noises. I see a person sitting across from me. Out of these unconnected sensations I construct a narrative. The red and white checkered pattern is a window shade. The green colors are foliage outside the window. The noise is the burning wood in the fireplace. The wooden beams tell me I am in Cold Spring Tavern in the mountains above Santa Barbara. The person sitting across from me is a composer from Germany.

Our sensory experiences are continuously and immediately analyzed and categorized within a cognitive context. This musical narrative builder is our “listening grammar” in operation, as Lerdahl (1988) called it. Our listening grammar is how we make sense of the sonic world.

Part of how we make sense of the world is that we anticipate the future. Indeed, the psychological foundation of music cognition is anticipation. As Meyer (1956) observed:

One musical event has meaning because it points to or makes us expect another event. Musical meaning is, in short, a product of expectation.

Thus a narrative chain can function because we inevitably anticipate the future. In a detailed study of musical anticipation, Huron (2006) described five stages of psychological reaction. They apply to music listening but also to any situation in which we are paying attention. These reactions occur very quickly–moment to moment–as we listen; they inform a narrative understanding of our experiences.

In electronic music especially, musical narrative often revolves around processes of sonic transformation. Consider, for example, the famous transformation seventeen minutes into Stockhausen’s Kontakte (1960) in which a tone descends in frequency in a flowing down and up-down manner until it dissolves into individual impulses, which then elongate to reform a continuous tone. Like a story from Ovid’s fantastic Metamorphosis (8 CE), in which nymphs transform into islands, we are fascinated by the strange fortunes of this sound.

Metaphorically, we can think of sounds as abstract characters that enter a stage, act out some behavior, and eventually leave the stage and our awareness. This sonic play is a multiscale process; it can describe one sound, a phrase, a section, or a whole piece. For example, if a unique sequence of events occurs over one minute at the start of a ten-minute piece, we call it a beginning. At the close of a piece, we call it the ending. Within the acting phase are a limitless realm of possible behaviors and interactions with other sounds.

How we interpret a sequence of musical events depends on our anticipation and our psychological reaction as to whether or not our expectations are met. As Huron (2006) noted:

Minds are “wired” for expectation…What happens in the future matters to us, so it should not be surprising that how the future unfolds has a direct effect on how we feel.

Sonic narrative is constructed by a succession of events in time, but also by the interaction of simultaneous sounds. This is the realm of generalized counterpoint. Do the sounds form a kind of “consonance” (resolution) or “dissonance” (opposition)? Is one sound a foil to the other? Does one serve as background while the other operates in the foreground? Does one sound block out another sound? Do the sounds move with one another (at the same time and in the same way) or are they independent? These contrapuntal interactions lead to moments of tension and resolution. As Varèse (quoted in Risset 2004) observed:

One should compose in terms of energy and fluxes. There are interplays and struggle between the different states of matter, like confrontations between characters in a play. Form is the result of these confrontations.

Figure 2. A frame from Andy Warhol’s film Empire (1964).

Even static structures can elicit the experience of narrative. I vividly recall the wide range of emotions I experienced watching Andy Warhol’s Empire (1964) for 45 minutes (Figure 2). This silent film consists of eight hours and five minutes of continuous footage of a single shot of the Empire State Building in New York City.

추상적인 소리 서술

서술은 무엇인가? 일반적인 의미로, 인간의 뇌가 실세계에서 얻은 경험을 가지고 미래를 기대하고 현재의 인식을 과거와 연관지으며 구성한 이야기이다. 우리는 끊임없이 감각적 경험들로부터 이야기를 만들어 낸다.

나는 앉아있다. 벽은 목재로 되어있다. 빨간 색과 흰 색의 체크무늬 형태가 보인다. 초록색이 보인다. 광역망 소음이 들린다. 나의 맞은 편에 한 사람이 앉아있다. 나는 이러한 서로 상관없는 감각 내용들을 가지고 하나의 서술을 만든다. 빨갛고 흰 체크무늬는 창문 블라인드이다. 초록색은 창문 밖 나뭇잎이다. 소음은 난로 안에서 타고있는 나무이다. 나무 받침 도리는 내가 산타 바바라 북쪽 산 속 콜드 스프링 터번(산중에 있는 오두막집 카페)에 있다고 말한다. 내 맞은 편에 앉은 사람은 독일에서 온 작곡가이다.

우리의 감각 경험은 인지적 맥락 안에서 연속해서 즉각적으로 분석되고 분류된다. 레르달(Lerdahl 1988)이 이른 바에 의하면, 이러한 음악적 서술을 짓는 것은 현재 시행중인 우리의 “청취 문법”이 된다. 우리의 청취 문법은 우리가 어떻게 소리세계를 이해하느냐 하는 것이다.

우리가 미래를 예상하는 것이 이 세계를 어떻게 이해하는지의 한 부분이 된다. 실제로, 음악 인지의 심리학적 토대는 이러한 기대감이다. 마이어(Meyer 1956)가 주목하였듯:

하나의 음악적 사건은 이것이 또 다른 사건을 암시하거나 우리가 이를 기대하도록 만듦으로써 의미를 갖는다. 요컨대, 음악적 의미는 기대의 산물이다.

따라서 우리가 미래를 예측하는 것이 불가피하기 때문에 서술적 연쇄가 작용하게 되는 것이다. 음악적 기대감에 대한 상세한 연구로, 휴론(Huron 2006)은 다섯 단계로 심리적 반응을 기술하였다. 이들은 음악청취 뿐 아니라 우리가 주목하고 있는 어떤 상황에도 적용된다. 이러한 반응들은 우리가 청취할 때 매우 빠르게-순간순간-일어나며, 우리가 경험하는 것들의 서술적 이해를 돕는다.

특별히 전자 음악에서, 음악적 서술은 소리 변형 과정을 중심으로 흐르는 경우가 많다. 한 음이 흘러내리다 다시 오르내리는 방식으로 음고를 하향했다가 충격적 사운드를 만나 흩어지고는, 다시 길게 늘어져 하나의 지속음으로 변모하는 스톡하우젠의 『콘탁테』(1960) 속 그 유명한 십 칠 분 변형의 예를 생각해보라. 요정이 섬으로 둔갑하는 오비디우스의 기가 막힌 시 『변신이야기』(8세기)의 줄거리에서처럼, 우리는 소리의 기이한 운세에 매혹된다.

비유적으로, 우리는 소리를 무대에 들어와 어떤 행위를 하고 결국 무대와 우리의 관심에서 떠나게 되는 등장인물로 생각할 수 있다. 소리 연극은 여러 크기의 것들을 다중적으로 처리한다; 하나의 소리나 악구, 악절, 곡 전체를 그려낼 수 있다. 예를 들어, 십 분짜리 작품의 시작에서 한 특유의 사건이 일 분 넘게 계속될 때, 우리는 이를 도입이라 부른다. 곡의 끝에서는 이를 결말이라 부를 것이다. 연주가 진행되는 동안에 다른 소리와의 가능한 행위와 상호작용이 제한없는 세상이 펼쳐진다.

음악적 사건이 연속되는 것을 어떻게 해석하느냐는 이에 대한 우리의 기대감과 그 기대를 충족하느냐 않는냐에 따른 우리의 심리적 반응에 달려있다. 휴론(Huron 2006)이 지적하였듯:

마음은 기대하는 것에 “초조해”한다…미래에 일어나는 일이 우리에게는 중요한 문제이기 때문에, 미래가 어떻게 펼쳐지느냐가 우리가 감정에 직접적인 영향을 준다는 것은 당연하다.

소리 서술은 시간에 따른 사건의 연속뿐 아니라 동시에 울리는 소리의 상호작용으로도 구성된다. 이는 보편적인 대위법의 영역과 같다. 이 소리들이 일종의 “협화”(해결)나 “불협화”(대립)를 이루는가? 이 소리는 다른 소리를 잘 부각시켜주는가? 어떤 소리는 배경의 역할을 하고 다른 소리는 주요음으로 작용하는가? 저 소리는 다른 소리를 잘 막아내었는가? 소리들이 함께 움직이는가(동시에 같은 방향으로), 아니면 서로 독립적인가? 이러한 대위적 상호작용은 긴장과 해결의 순간을 이끌어낸다. 바레즈(Risset 2004에서 인용됨)가 주목하였듯:

작곡 작품에는 에너지와 끊임없는 변화가 필요하다. 연극에서 등장인물들이 대치하듯, 다른 상태의 사안들 간에 상호작용과 분투가 있는 것이다. 형식은 이러한 대치의 결과이다.

그림 2. 앤디 워홀의 영화 『엠파이어』(1964)의 한 장면..

정적인 구성도 명확한 서술을 경험할 수 있다. 나는 앤디 워홀의 『엠파이어』(1964)를 45분동안 보면서 느꼈던 넓은 감정의 폭을 지금도 생생히 상기시킬 수 있다(그림 2). 이 무성 영화는 뉴욕 시에 있는 엠파이어 스테이트 빌딩를 단독으로 지속 촬영한 영상을 여덟 시간 오 분 간 보여주는 구성이다.

Morphology, Function, Narrative

Design is a funny word. Some people think design means how it looks. But of course, if you dig deeper, it is really how it works. – Steve Jobs

What is the relationship between morphology, structural function, and narrativity in music? Let us start with a simple example. The morphology of a table is its shape–how it looks. Let us define its structure or organization as the way that the component parts are interconnected, how the legs attach to the top. As the biologist Thompson (1942) observed:

A bridge was once upon a time a loose heap of pillars and rods and rivets of steel. But the identity of these is lost, just as if they had fused into a solid mass once the bridge is built. …The biologist as well as the philosopher learns to recognize that the whole is not merely the sum of its part… For it is not a bundle of parts but an organization of parts.

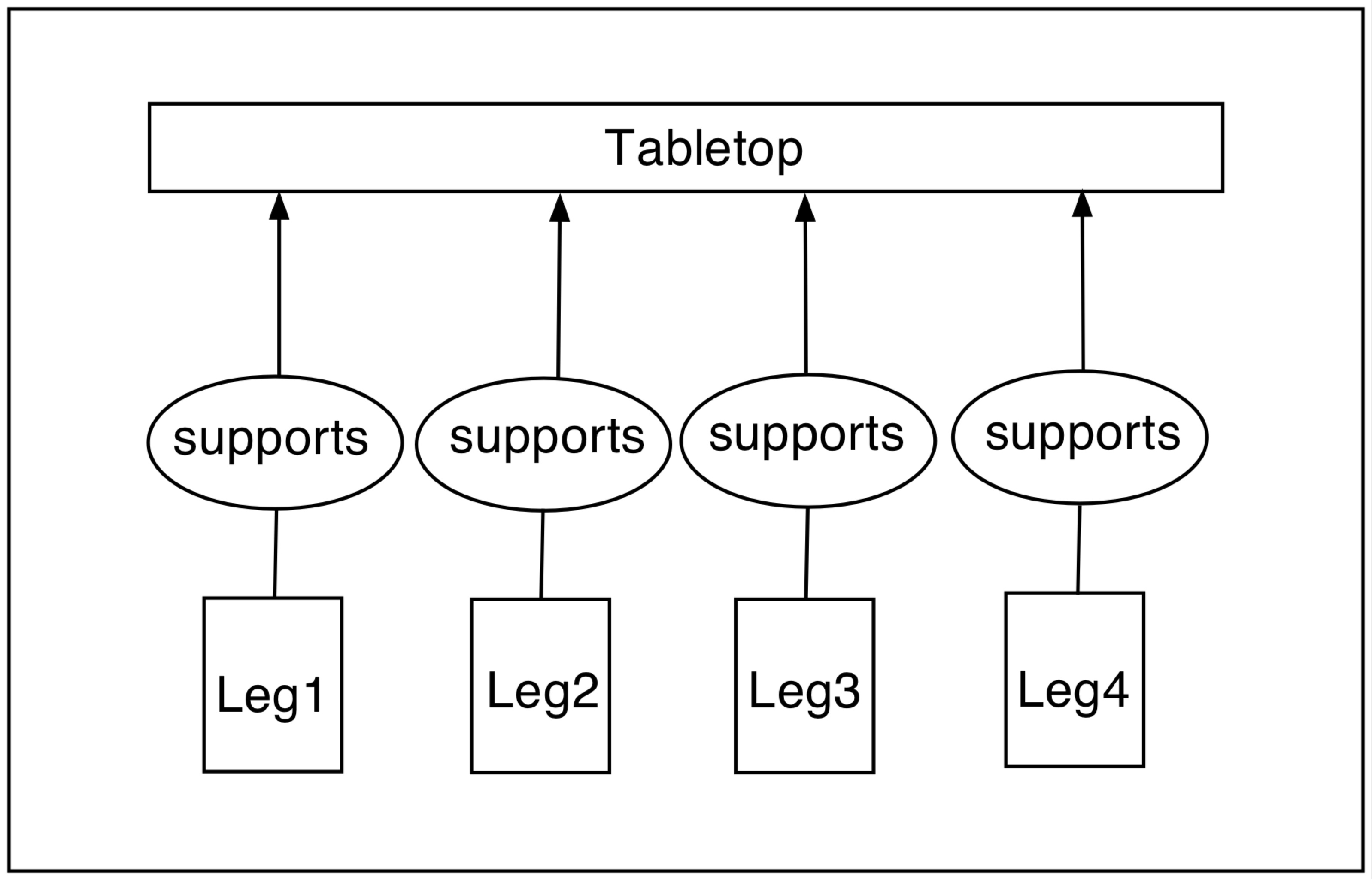

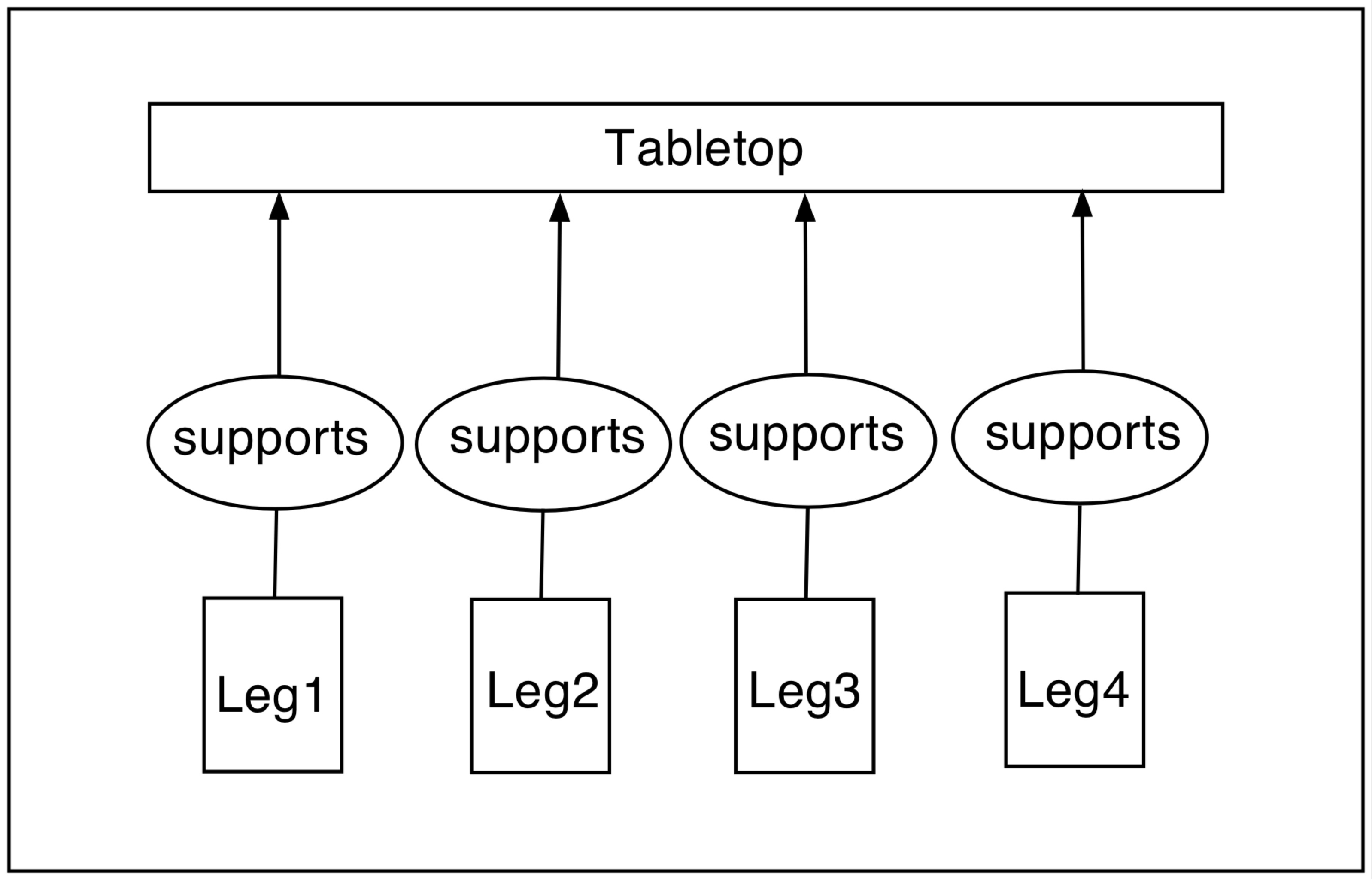

Figure 3. Functional representation of a table.

Figure 3 shows a simple diagram of the structure of a table. The oval elements connect and describe a functional relationship between the component parts. The basic function of the entire table is to support things placed on its top, but it can have other functions such as serving as a portable table, extendable table, or visual accent, etc. Thus there can be more than one functional relationship between two parts. For example, a table leg in steel might serve an aesthetic function of being a visual/material contrast to a marble tabletop.

Morphology in music is a pattern of time-frequency energy. Music articulates myriad structural functions: temporal, spatial, timbral, melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, etc. It can also serve and articulate social and cultural functions in all manner of rites and rituals, from the street to the palace.

Structural function refers to the role that an element (on any time scale) serves in relation to a composition’s narrative structure. It was defined abstractly by music theorist Wallace Berry (1987) as follows:

To see structural function in music…is to see, in general, three possibilities: increasing intensity (progression), subsiding intensity (recession), and unchanging event succession (stasis).

Structural functions play out not just in pitch and rhythm but in all of music’s features, as Berry (1987) observed:

There are “dissonances” and resolutions in all of music’s parameters.

Accordingly, to serve a structural function, an element either increases intensity, decreases intensity, or stays the same. Processes such as increasing intensity (heightening tension) and decreasing intensity (diminishing tension) are narrative functions. To give an example, an explosion at the close of part one of my composition Never (2010) releases energy and fulfills a narrative function as: The End.

Changes in intensity imply trends, and therefore imbue directionality. Of course, reducing all musical functionality to its effect on “intensity” begs the question of how this translates to specific musical parameters in actual works. Berry’s book explores this question through analytic examples. The analysis can be quite complicated. Real music plays out through the interplay of multiple parameters operating simultaneously and sometimes independently. Stasis in one dimension, such as a steady rhythmic pattern that serves a structural function of articulating a meter, can serve as a support for a process of increasing intensity in another dimension, such as the structural function of a crescendo, while another dimension undergoes a process of decreasing intensity.

Ultimately, structural functionality concerns the role and thereby the purpose of an element within a specific musical context. The context is extremely important. As Herbert Brün (1986) observed:

Composition generates whole systems so that there can be a context which can endow trivial “items” and meaningless “materials” with a sense and a meaning never before associated with either items or materials.

To use an architectural analogy, a wooden beam that supports the roof of a traditional house would serve only a decorative function in the context of a steel skyscraper. Context is the key to meaning.

형태론, 기능, 서술

디자인이란 기이한 단어다. 사람들이 디자인을 생각한다는 것은 어떻게 생겼는지를 뜻한다. 하지만, 좀 더 깊게 파고 들어가 보면, 실제로는 그것이 어떻게 기능하는가임을 깨닫게 된다. – 스티브 잡스

음악에서 형태론과 구조적 기능, 서술성의 관계란 무엇일까? 간단한 일례로 시작해보자. 책상의 ‘형태론’은 이것의 모양-어떻게 생겼나-이다. 각 구성 요소들이 연결된 방식, 즉 책상다리가 상판에 어떻게 붙여졌는지에 따른 이것의 ‘구조’나 ‘체계성’을 정의해보자. 생물학자 톰슨(Thompson 1942)이 말하였듯:

다리는 한 때 기둥과 막대, 철못이 헐겁게 합쳐진 무더기로 여겨졌다. 그러나 그저 다리를 지을 때 한 덩어리로 단단히 결합해 왔던 것처럼, 그런 이미지는 사라졌다. …생물학자뿐 아니라 철학자들도 전체는 단순히 부분의 합이 아니라는 것을 안다… 왜냐하면 이는 부품들의 ‘묶음’이 아니라 그들의 ‘체계적인 조직체’이기 때문이다.

그림 3. 책상의 기능 구도.

그림 3은 책상의 구조를 간단한 도식으로 보여준다. 타원형 요소가 개별 부품 사이의 기능적 관계를 연관지어 묘사한다. 상 전체의 기본적인 기능은 책상 상판에 올려둘 물건을 지탱하는 것이지만, 이동형이나 확장형 책상, 혹은 강조적인 인테리어 효과처럼 다른 기능을 가지기도 한다. 그래서 부분들의 사이에는 하나 이상의 기능적 관계성이 존재할 수 있다. 예를 들어, 철제 책상 다리는 대리석 상판과 시각적/소재적 대조를 이루는 것으로 미학적 기능을 할 지도 모른다.

음악에서의 형태론은 시간-주파수 에너지의 패턴으로 이루어진다. 음악은 시간적, 공간적, 음색적, 선율적, 화성적, 리듬적 등 무궁무진한 구조적 기능을 표현한다. 온갖 방식의 의례와 의식 절차로, 거리에서부터 왕궁까지, 사회 문화적 기능을 수행하고 표명하기도 한다.

구조적 기능이란 (어떠한 시간 영역에 관한) 한 요소가 작품의 서술 이야기 구조와 연관짓도록 역할을 수행하는 것을 말한다. 음악 이론가 월리스 베리(Berry 1987)가 이를 관념적으로 정의하였는데, 다음과 같다:

음악의 구조적 기능을 본다는 것은…일반적으로 상승하는 강도(발전), 하강하는 강도(쇠퇴), 불변하는 사건의 지속(유지)의 세 가지 가능성을 본다는 뜻이다.

구조적 기능은 단순히 음고나 리듬에서뿐 아니라 음악의 모든 특성에서 그 역할을 다한다. 베리(Berry 1987)가 주시하였듯:

모든 음악 요소요소에 “충돌”과 해결이 있다.

따라서, 구조적 기능을 수행하려면, 한 요소가 강도를 높이고 내리거나, 혹은 같은 곳에 머무르면 된다. 강도 상승(긴장을 높임)이나 강도 하강(긴장을 낮춤)과 같은 작업은 서술적 기능이다. 한 예로, 나의 작품 『네버Never』(2010)의 마지막 부분에 나타나는 폭발은 에너지를 발산하면서 서술적 기능을 수행한다, 끝이라는.

강도가 변화하면서 추세를 만들고, 이래서 방향성이 고취된다. 물론, 모든 음악적 기능성을 “강도”의 효과로만 축소하는 것은 어떻게 강도 변화가 실제 작품의 개별 음악 요소로 소화될 것인가 하는 질문을 할 수밖에 없게 한다. 베리의 책에서는 분석 예시들을 통해 이 질문에 대해 탐구한다. 이 분석은 상당히 난해할 것이다. 진짜 음악은 동시에 한꺼번에, 때때로는 독립적으로 움직이는 다수의 요소들이 상호작용하며 연주를 완성한다. 구조적 기능으로서 박자를 명시하는 일관된 리듬 패턴처럼 일차원적 유지 상태는 크레센도의 구조적 기능과 같이 또 다른 차원의 강도 상승 과정을 도와주는 기능을 할 수 있고, 반대로 다른 차원은 강도가 하강하는 결과를 얻게 된다.

궁극적으로, 구조적 기능은 음악의 특정한 문맥에서 한 요소의 역할과 그 역할에 의한 목적에 관한 것이다. 이 문맥은 심각하게 중요하다. 허버트 브륀(Brün 1986)이 말하길:

작곡은 전체 시스템을 통해 사소한 “사항”과 의미없는 “소재”에 이전에는 그 사항이나 소재와는 연관되지 않았던 합리성과 의미를 부여할 만한 문맥을 만들어내는 것이다.

건축학적 비유를 사용하자면, 전통적인 집 지붕을 받쳐주는 나무 도리는 철제 고층 건물에서라면 장식적인 기능밖에 할 수 없을 것이다. 문맥이 의미의 핵심이다.

Sonic Causality

A sonic narrative consists of chains of events. These chains can create an illusion of cause and effect, as if a subsequent event was the inevitable consequence of an antecedent event. One way teleology can emerge in a musical narrative is by the design of chains of causal relationships.

Let us distinguish two distinct uses of the term “causality” in the context of electronic music. In the acousmatic discourse, causality is concerned with identifying the source that generated a given sound, i.e., what is its origin? By contrast, our interest concerns a different issue, the idea that one sound appears to cause or give rise to another in a narrative sense, what Lars Gunnar Bodin (2004) called causal logic. What if one sound was the necessary antecedent that appears to cause a consequent sound? We see this effect in the cinema, where a succession of sounds–spliced and layered together–lend continuity to a visual montage (e.g., footsteps + yell + gunshot + scream + person falls to the ground). “Appears to cause” is the operative phrase; my use of the term “causality” is metaphorical. As in the cinema, we seek only an illusion of causality, suggested by a progression of events that indicate a direction leading to some inevitable result. As I wrote about Half-life, composed in 1999:

As emerging sounds unfold, they remain stable or mutate before expiring. Interactions between different sounds suggest causalities, as if one sound spawned, triggered, crashed into, bonded with, or dissolved into another sound. Thus the introduction of every new sound contributes to the unfolding of a musical narrative. (Roads 2004)

As a sonic process emerges out of nothing, it may spawn additional musical events. These events, be they individual particles or agglomerations, interact with existing events, setting up a chain of implied causalities. Two sounds can converge or coincide at a point of attraction or scatter at a point of repulsion, leading to a number of con-sequences:

Fusion - multiple components fuse into a single sound

Fission - sounds split into multiple independent components

Arborescence - new branches split off from an ongoing sound structure

Chain reaction - sequences of events caused by a triggering event

An impression of causality implies predictability. If listeners are not able to correlate sonic events with any logic, the piece is an inscrutable cipher.

청각적 인과성

소리 서술은 사건의 연속으로 구성된다. 이러한 연쇄는, 뒤따르는 사건이 앞선 사건의 불가피한 결과인 듯 원인과 결과라는 환상을 만들어내게 된다. 음악적 서술에서 목적성을 부각시키는 한 가지 방법이 연속적인 인과 관계를 기획하는 것이다.

전자 음악의 문맥에서 “인과성”이라는 용어의 두 가지 분명한 쓰임새를 구분해보자. 음향음악에 관한 이야기에서, 인과성은 그 소리를 발생한 출처를 식별해내는 것과 관련있다, 즉 소리의 근원이 무엇인가? 대조적으로, 우리는 다른 이슈, 그 소리가 서술적 의미로 어디서 나타났으며 또 다른 소리를 일으킬 것으로 보인다는 생각에 관심을 두는데, 라르스 구나 보딘(Bodin 2004)은 이를 “인과적 논리”라 부른다. 어떤 소리가 뒤따르는 소리를 일으킬 것으로 보이는 반드시 필요한 선행 조건이라면 어떨까? 우리는 이러한 효과를 영화에서 볼 수 있다. 이어붙이고 겹겹이 쌓인-소리의 연쇄는 시각적인 짜집기 편집(예를 들어, 발소리 + 고함 + 총소리 + 비명 + 사람이 쓰러짐)에 연속성을 더한다. “일으킬 것으로 보인다”는 말은 실질적인 구절이고; 내가 사용한 “인과성”은 은유적 단어이다. 영화에서처럼, 우리는 그저 사건이 연속되면서 어떤 방향을 제시하고 이에 따라 어떤 불가피한 결과로 이끌리게 되는 인과성의 환상을 추구할 뿐이다. 내가 1999년 작품 『반감기 Half-life』에 대해 쓴 글에 의하면:

소리들이 출현하고 전개하면서, 그들은 안정적으로 유지되거나 변화하고 그 후 사라진다. 서로 다른 소리들 간의 상호작용 중 어떤 소리는 산란하고, 촉발되며, 충돌하거나 결합하고, 또 다른 소리로 녹아 들어가는 듯한 인과관계를 연상시킨다. 그래서, 모든 새로운 소리의 출현은 음악적인 서술을 전개하는데 기여한다. (Roads 2004)

소리의 과정이 무에서 생성되면서, 추가적인 음악적 사건을 낳기도 한다. 이러한 사건은, 개별적인 입자이든 집합체의 덩어리이든 간에, 기존의 사건들과 상호작용하며 시사된 암시성을 연속해서 만들어 나간다. 두 개의 다른 소리는 ‘이끌리는 지점’에 수렴되거나 부합하거나, ‘밀려나는 지점’에서 흩어지면서 수많은 귀결점들로 이어지게 된다.

융합 – 단 하나의 소리로 융합되는 여러 요소들

분열 – 다수의 개별 요소로 쪼개지는 소리들

나뭇가지상 – 기존의 소리 구조에서 떨어져 나온 새로운 가지들

연쇄 반응 – 사건의 촉발로 야기된 후속 사건들

인과성이 주는 인상으로 예측가능함이 시사된다. 청자가 음악적 사건을 어떠한 논리와도 연관짓지 못한다면, 그 작품은 불가해한 암호에 지나지 않는다.

Nonlinear or Variable Narrative

A film should have a beginning, middle, and end, but not necessarily in that order. – Jean-Luc Godard (1966)

The term linear narrative has often been applied to a story with a beginning that introduces characters or themes, followed by tension/conflict resulting in a climax/resolution and final act. A linear narrative presents a logical chain of events; events progress and develop, they do not just succeed one another haphazardly.

Contrast this with so-called nonlinear interactive media, where each participant can choose their own path through a network. A classic example is a gallery exhibit, where each person can view artworks in any order. Notice, however, the linearity within the nonlinearity. Each person in a gallery views a “linear” sequence of images. It is merely different from what another viewer sees. Moreover, these experiences are taking place in time, which according to the metaphor timeline, is a linear medium. What makes a medium “nonlinear” is its variability–everyone can do it a different way–whether by chance or choice. Variable multipath narrative is perhaps a more descriptive term than “nonlinear narrative.”

Some would say that the experience of music is linear, in that it unfolds in time and different audience members have no choice in what they hear. Similarly, a book is read from the beginning to the end.

Yet filmmakers, composers, and novelists often speak of nonlinearity in the organization of their works, even if they are ultimately presented in the form of an unvarying single-path narrative. It is not necessary for a musical narrative to unfold in a linear chain. Artists use many techniques to break up or rearrange sequential narrative: ellipses, summaries, collage, flashback, flashforward, jump cut, montage, cut-up, and juxtaposition. Narrative emerges out of nothing other than adjacencies, as Claude Vivier (1985) observed:

My music is a paradox. Usually in music, you have some development, some direction, or some aim. . . I just have statements, musical statements, which somehow lead no-where. On the other hand, they lead somewhere but it's on a much more subtle basis.

Using digital media, sounds and images can play in any order, including backwards, sped up, slowed down, or frozen. Granulation can pulverize a speaking voice into a cloud of phonemes, transforming a story into an abstract sonic narrative.

Moreover, music is polyphonic: why not launch multiple narratives in parallel? Let them take turns, interrupt each other, unfold simultaneously, or twist in reverse. The possibilities are endless. As music psychologist Eric Clarke (2011) observed:

Music’s own multiplicity and temporal dynamism engage with the general character of consciousness itself.

Narrative design can be labyrinthine or kaleidoscopic, reflecting the true nature of consciousness and dreams.

Consider Luc Ferrari’s comments on the construction of his Saliceburry Cocktail (2002)

The Cocktail idea suggested that I hide things under one another. I took old elements, and since I didn’t want to hear some of them, I hid them under some elements that I also didn’t want to hear. And since I remembered some of the sounds, I also had no choice but to hide the images they evoked, and I had to hide some other realistic elements un-der synthetic sounds, and I had to dissimulate some of the synthetic sounds under some drastic transformations. Finally, I hid the structure under a non-structure or the other way around.

Sound Example 6.

Excerpt of Saliceburry Cocktail (2002) by Luc Ferrari.

Surprise is essential to a compelling narrative. Surprises are singularities that break the flow of continuous progression. The appearance of singularities implies that, like a volcano, the surface structure is balanced on top of a deeper layer that can erupt at any moment. If we look at what caused it, it is the will of the composer at the helm of a sonic vessel. The voyage of this vessel, as communicated by the sound pattern it emits, traces its narrative.

비순차적 혹은 다양한 서술

영화는 시작과 중간, 결말이 있어야 하지만, 그 순서를 지킬 필요는 없다. – 장-루크 고다르(Jean-Luc Godard 1966)

‘순차적 서술’이라는 용어는 등장인물과 주제를 소개하는 도입부 이후, 긴장/갈등이 초래하는 절정/해결과 마지막 장으로 이어지는 이야기에 종종 적용되곤 한다. 순차적 서술은 논리적으로 연속되는 사건들을 제공한다; 이 사건들이 전개되고 발전하는데 있어, 이유없이 무턱대고 이어지는 법이 없다.

이를 네트워크를 이용해 개별 사용자가 각자의 경로를 선택하는 소위 ‘비순차적인 인터랙티브 미디어’와 대조해보라. 한 고전적인 예로 각자가 임의의 순서로 작품을 관람하는 갤러리 전시회가 있다. 하지만, 비순차성 내의 순차성을 주의하라. 갤러리에 있는 각 관람자는 “순차적으로” 연속해서 그림을 본다. 그저 다른 관람객이 보는 순서와 다를 뿐이다. 더욱이, 이러한 경험은 시간의 흐름에 따라 발생하며, 이는 ‘시간표’를 따르는 것과 같이 직선적인 도구에 불과한 것이다. 우연에 의한 것이든 선택에 의한 것이든 누구나 다른 방식으로 시도할 수 있는 다양성이 “비순차적”인 수단이 되는 것이다. 아마 ‘다양하게 여러 경로를 갖는 서술’이야말로 “비순차적 서술”보다 더 기술적인 용어라 할 것이다.

어떤 사람은 음악이 시간에 따라 진행하면서 각각의 청자가 무엇을 들을지 달리 선택할 수 없다는 점에서 음악을 듣는 것은 순차적이라 여길 것이다. 유사하게, 책도 앞장부터 끝장으로 읽도록 되어있다.

그런데 영화제작자나 작곡가, 소설가들은 그들의 작품이 비순차적인 조직 체계를 띈다는 이야기를 종종 한다. 결과적으로는 한결같이 단일한 경로의 서술을 제시해놓고 말이다. 음악적 서술이 순차적으로 연결될 필요는 없다. 예술가는 순차적인 서술을 깨고 재배치할 수 있는 여러 기법들-생략, 요약, 모음, 회상, 미래로 건너뜀, 급전환, 짜집기, 끼워넣음, 병치시킴-을 사용한다. 서술은 근접한 것에 의하기 보다는 아무 근거없이 무에서 창작되는데, 클로드 비비에(Vivier 1985)는 이렇게 말한다:

내 음악은 모순적이다. 보통 음악에서는, 어느 정도의 발전이나 방향, 향하는 지점이 있다… 내 작품은 진술, 음악적 진술을 할 뿐이고, 어쨌든 어디로도 향하지 않는다. 반면에, 그 진술들이 어디론가로 이끌기는 하지만, 그 근거는 매우 소소하다.

디지털 매체를 사용하면, 소리와 이미지는 되감기나 빠르게 혹은 느리게, 정지 기능을 포함하여 어떤 순서로든 재생될 수 있다. 입자화Granulation를 통해 말소리를 분쇄해 음소의 구름 덩어리로 만들어, 한 이야기를 추상적인 소리 서술로 변형시킬 수 있다.

더욱이, 음악은 다중적이다: 여러 서술을 다중적으로 병행하면 왜 안되겠는가? 그들을 번갈아 배치하고, 서로 끼여들고, 동시에 전개시키거나, 거꾸로 비틀어보자. 가능성은 무궁무진하다. 음악심리학자 에릭 클라크(Clarke 2011)가 말한 바:

음악이 내포한 다중성과 시간적 역학성은 의식 그 자체의 일반적인 특성과 맞물린다.

서술을 기획하는 것은 의식과 꿈의 실체를 반영하는 미로나 만화경과 같다.

루크 페라리가 그의 『살리스베리 칵테일』(2002)의 구성에 관해 언급했던 말을 고려해보라.

나는 칵테일이라는 아이디어로 어떤 것들을 서로의 아래 숨기는 것에 대해 생각하게 되었다. 기존 요소들을 쓰되, 일부 원치 않는 것들이 있어서, 그것들을 어떤 요소들 밑에 숨겼는데 그 요소들 중 일부도 듣고 싶지 않은 소리들이 있었다. 그 소리의 일부는 내가 기억하고 있는 소리들이어서, 그것들이 상기시키는 이미지들을 숨기지 않을 수 없었고, 그래서 합성된 소리들 아래 몇몇 사실적인 요소들을 숨겼고, 합성된 소리의 일부는 몇몇 과감한 변형 요소들 아래 감추었다. 결국, 나는 작품의 구조를 거꾸로 된 방향으로 비구조의 밑으로 넣어 이를 위장하였다.

음악 6.

루크 페라리의 『살리스베리 칵테일』(2002)의 발췌본.

뜻밖의 사건은 설득력 있는 서술 이야기에서 매우 중요하다. 깜짝 놀라게 되는 순간은 연속되는 진행의 흐름을 깨뜨리는 특이점이 된다. 특이점이 나타난다는 것은, 화산처럼, 언제라도 분출할 수 있는 하층 위에서 표면층 구조가 균형을 이루고 있다는 것을 시사한다. 무엇인가가 야기되었다면, 그것은 소리라는 배를 조종하는 작곡가의 의지인 것이다. 이 배의 항해는, 이가 내뿜는 소리 패턴으로 소통하는 바를 따라, 서술 이야기를 쫓는다.

Antinarrative Strategies

Certain composers, most notably John Cage, reject narrative as an organizing principle. Yet a narrative impression is not so easily disposed. In this sense, narrative is like form, something rather hard to extinguish. As Earle Brown (1967) wrote:

If something were really formless, we would not know if its existence in the first place. It is the same way with “no con-tinuity” and “no relationship.” All the negatives are pointing at what they are claiming does not exist.

The mind is –searching for patterns even in pure noise. Anyone who listens Stockhausen’s moment form works such as Kontakte (1960) or Momente (1964) hears teleological processes, patterns of increasing and decreasing intensity, convergence/divergence, coales-cence/distintegration, and causal illusions, all elements of narrative. While the macro form is nondirectional, on other time scales we hear many familiar narrative elements: openings, development, cadences, counterpoint, transitions, etc. In any case, perceived randomness takes on well-known narrative identities: a series of unrelated juxtapositions is predictably chaotic, and white noise is predictably unchanging.

반서술적 전략

가장 유명하게는 존 케이지를 비롯한 몇몇 작곡가들은 서술을 작품 구성의 원리로 보는 것을 거부한다. 그러나 서술적인 인상은 그렇게 쉽게 없어지지는 않는다. 이런 의미에서, 서술은 오히려 쉽게 사라지지 않는 어떤 것, 형체와도 같은 것이다. 얼 브라운(Brown 1967)이 쓴 바에 따르면:

어떤 것이 실제로 아무 형체가 없다면, 우리는 애초에 이것의 존재를 알 수 없었을 것이다. “무연속성”과 “무관계성”의 경우도 마찬가지다. 모든 부정적인 단어는 그것이 존재하지 않는다고 주장하는 것을 가리키고 있다.

우리의 마음은 아포페니아-단순한 소음에서조차 의미를 찾으려는 심리-적이다. 스톡하우젠의 『콘탁테』(1960)나 『모멘테』 (1964)에서와 같이 순간이 연속되는 형식moment form 작품을 듣는 누구라도 목적론적 과정과 강도가 상승하거나 하강하는 패턴, 집중과 분열, 융합과 분해, 인과적 환상의 모든 서술적 요소들을 듣게 된다. 큰 규모의 형식에서는 무지향적이지만, 다른 시간적 차원으로서 우리는 서두와 발전, 종지, 대위적 기법, 경과구 등 많은 친숙한 서술적 요소들을 들을 수 있다. 어떤 경우라도, 임의의 인식된 것들은 모두 친숙한 서술적 특성으로 연결될 수 있다: 관계없는 것들을 병렬한다면 당연히 혼란스러워질 것이며, 백색소음은 예상대로 변화없는 상황을 만들 것이다.

Synthesizing Narrative Context

Intimately related to the concept of narrative is the prin-ciple of context. Narrative context–on whatever time scale–determines the structural function and appropriateness of sound material. Only a contextually appropriate sound serves narrative structure. We see here the deep relationship between materials at lower levels of structure and the morphology of the higher-level context. Inappropriate sound objects and dangling phrases inserted into a structure from another context work against their surroundings. If they are not pruned out of the composition, their presence weakens the structural integrity of the piece. Even a small anomaly of this kind can loom large in the mind of listeners. An inappropriate sound object or phrase can cancel out the effect of surrounding phrases, or call into question the effectiveness of an entire composition.

What determines the “inappropriateness” of a sound or phrase? This is impossible to generalize, as it depends entirely on the musical context. It is not necessarily a sharp juxtaposition–juxtapositions can be appropriate. It could be a sound that is unrelated to the material in the rest of the piece or an aimless section that drains energy rather than building suspense.

For fear of inserting an inappropriate element into a piece, one can fall into the opposite trap: overly consistent organization. This condition is characterized by a limited palette of sounds and a restricted range of operations on these sounds. A hallmark of the “in the box” mindset, an overly consistent composition can be shown to be “coherent” in a logical sense even as it bores the audience.

In certain works, the synthesis of context is the narrative. For example, in Luc Ferrari’s brilliant Cycle des souvenirs (2000), the composer is a master of fabricating context from unrelated sources: synthesizers, women speaking softly, bird and environmental sounds, a drum machine, and auditory scenes of human interaction around the world. In Ferrari’s hands, these disparate elements magi-cally cohere. Why is this? First, the sounds themselves are exceptional on a surface level and their mixture is refined. On a higher structural level, we realize that the various elements each have a specific function in inducing a sensibility and mood. The combination serves to induce a kind of trance–made with everyday sounds that contextualize each other. When new sounds are introduced they are often functional substitutions for sounds that have died out, thus maintaining the context. For example, the work is full of repeating pulses, but from a wide variety of sound sources. When one pulse dies out, another eventually enters, different in its spectromorphology, but retaining the structural function of pulsation.

서술적 문맥 통합하기

서술의 개념은 문맥의 원리와 밀접하게 연관된다. 서술적 문맥-어떤 시간의 규모에서든-이 구조적 기능과 소리 재료의 타당성을 결정짓는다. 문맥에 적절한 소리만이 서술적 구조의 역할을 할 수 있다. 우리는 여기서 구조의 낮은 단계에 있는 재료와 높은 차원의 문맥으로서 형태론 사이의 깊은 관계성을 알 수 있다. 어울리지 않는 소리체나 위태로운 불완전 악구를 그 문맥에 맞지 않는 다른 구조에 끼워 넣는다면 그들 주변의 소리에 반하게 될 것이다. 그것들을 작품에서 쳐내지 않으면, 그들의 존재가 작품의 구조적인 짜임새를 약화시키게 된다. 이런 류의 작은 이변 하나도 청자들의 감상에는 크게 비칠 수 있다. 부적합한 소리체나 구절이 그 주변 구절들의 영향력을 상쇄하고 작품 전체의 유효성에 대한 문제마저 일으킬 수 있다.

소리나 구절의 “부적절함”은 어떻게 판단할까? 이는 전적으로 음악적 문맥에 달려 있으므로, 일반화는 불가능하다. 반드시 예리한 병치를 해야하는 것은 아니다-병치는 상관없다. 작품 내 다른 부분에 있는 재료들과 연관성이 없는 소리, 혹은 긴장감을 높이기 보다는 있던 에너지마저 약화시키는 가벼운 섹션이 문제가 될 수 있다.

작품에 부적절한 요소가 생기면 어쩌나 하는 두려운 마음에, 지나치게 일관적인 짜임새로 정반대의 덫에 걸리기도 한다. 이러한 상황은 사용한 소리의 음색이 다양하지 않고, 그 소리를 작업하는 범위 또한 제한적인 것이 특징이다. “상자 안” 방식의 보증마크로서, 몹시 일관적인 짜임새는 청중을 지루하게 함에도 논리적으로는 “투철한” 작품으로 간주되곤 한다.

어떤 작품에서는, 문맥의 융합으로 서술이 된다. 예를 들어, 루크 페라리의 훌륭한 작품 『기억의 순환』(2002)에서는, 작곡가가 신서사이저와 작게 말하는 여자들, 새와 그 주변의 소리, 드럼 머신, 세계 곳곳에서 사람들이 상호작용하는 장면의 서로 상관없는 재료들에서 그 문맥을 조립해내는 달인으로 역할한다. 페라리의 손길로, 이질적인 요소들이 마법처럼 논리정연하게 응집한다. 왜 그럴까? 첫째, 이 소리들은 일차적으로는 그 자체로 별개의 것이지만, 조립된 결과물은 정제된 것이다. 더 높은 구조적 차원에서, 우리는 여러 다양한 요소들이 어떤 감정과 분위기를 유도하는 데 각자 그 나름의 특정한 기능을 한다는 것을 알 수 있다. 이 조합은 -일상의 소리들이 서로의 문맥을 맞춰 조립되면서- 일종의 몰입경까지 귀납시켜 줄 수 있다. 새로운 소리가 출현할 때 주로 사라진 소리의 기능을 대체하는 경우가 많은데, 그렇게 문맥을 이어나가게 된다. 예를 들어, 펄스를 반복하는 것이 전부이면서, 그 소리 재료는 매우 다양한 작품이 있다고 해보자. 한 펄스가 사라지면, 그제야 다른 펄스가 나타나는데, 음향형태분석학적으로는 다른 것이지만, 박동이라는 구조적인 기능은 유지된다.

Humor, Irony, Provocation as Narrative

Narrative context can be driven by humor, irony, and provocation. These need not be omnipresent–many seri-ous works have humorous moments.

What is the psychology of humor in music? Huron (2006) describes it as a reaction to fear:

When musicians create sounds that evoke laughter… they are, I believe, exploiting the biology of pessimism. The fast-track brain always interprets surprise as bad. The uncer-tainty attending surprise is sufficient cause to be fear-ful…But this fear appears and disappears with great rapidity and does not involve conscious awareness. The appraisal response follows quickly on the heels of these reaction re-sponses, and the neutral or positive appraisal quickly extin-guishes the initial negative reaction…In effect, when music evokes one of these strong emotions, the brain is simply realizing that the situation is very much better than first impressions might suggest.

Huron (2006) enumerates nine devices that have been used in music to invoke a humorous reaction, including material that is incongruous, oddly mixed, drifting, dis-ruptive, implausible, excessive, incompetent, inappropri-ate, and misquoted. Humor can be derisive. As Luc Ferrari (quoted in Caux 2002) observed:

To be serious in always working in derision is a permanent condition of my work. I am always preciously outside of an-ything resembling the idea of reason. Derision lets me dis-turb reason: who is right, who is wrong? It is also a question of power.

Dry humor is omnipresent in Ferrari’s music, for example in the incessantly repeating “Numéro quatro?” in Les anecdotiques (2002), or the changing of the guard se-quence in Musique promenade (1969) with its absurdly contrasting sound layers.

Sound 7.

Excerpt of "Numéro quatro" from Les anecdotiques (2002) by Luc Ferrari.

Charles Dodge’s humorous Speech Songs (1973) featured surreal poems by Mark Strand as sung by a computer. As the composer (2000) observed:

I have always liked humor and had an attraction to the bi-zarre, the surreal. These poems were almost dream-like in their take on reality. So that made me feel very at home somehow. This unreal voice taking about unreal life situa-tions was very congruent. The voices are … cartoon-like and that pleased me.

Dodge’s Any Resemblance is Purely Coincidental (1980) warps the voice of Enrico Caruso to both humorous and tragic effect.

Sound 8.

Excerpt of Any Resemblance is Purely Coincidental (1980) by Charles Dodge.

A camp sense of humor prevails in the electronic pop music of Jean-Jacques Perrey, such as his rendition of Flight of the Bumblebee (1975) featuring the sampled and transposed sounds of real bees.

Irony is a related narrative strategy, letting music comment on itself and the world around it, often with humorous effect. Many techniques communicate irony: absurd juxtapositions, quotations of light music, and ex-aggerations, for example. Irony can also be conveyed in extrinsic ways such as in titles and program notes. An example is Stockhausen’s 1970 program notes to the CBS vinyl edition of the Klavierstücken (CBS 32 21 0007). In the guise of documentation, the composer meticulously detailed all aspects of the recording, including the con-sumption habits of the pianist Aloys Kontarsky in the period of the recording sessions.

...[The pianist] dined on a marrow consommé (which was incomparably better than the one previously mentioned) 6 Saltimbocca Romana, lettuce; he drank 1/2 liter of Johan-nisberg Riesling wine; a Crêpe Suzette with a cup of Mocca coffee followed; he chose a Monte-Cristo Havana cigar to accompany 3 glasses of Williams-Birnengeist, with an ex-tended commentary on European import duties for cigars (praising Switzerland because of duty by weight) and on the preparation and packing of Havana cigars.

Another example of absurdist irony appears in John Cage’s Variations IV (1964) “For any number of players, any sounds or combinations of sounds produced by any means, with or without other activities.” The recording of the work unfolds as a Dadaesque collage that juxtaposes excerpts of banal radio broadcasts. These form a sarcastic commentary on American popular culture. Ironic re-sampling is a recurrent theme of artists influenced by the aesthetics of cut-up or plunderphonics (Cutler 2000).

Closely related to humorous and ironic strategies is provocation. Provocative pieces tend to divide the audi-ence into fans versus foes. As Herbert Brün (1985) noted:

We often sit in a concert and listen to a piece to which we do not yet have a “liking” relationship but of which we know already that it annoys the people in the row behind us–and then we are very much for that piece. I would sug-gest that my piece is just on a level where it invites you to a conspiracy with me and you like that. Yes, it annoys a few people in your imagination or your presence that you would like annoyed, and I am doing you this little favor.

Notice the two sides of the effect: some people enjoy the piece at least in part because they think others are an-noyed. Some artists are deliberately provocative; they seek to shock the audience. Shock is a well-worn strategy. Consider Erik Satie’s Vexations for piano (1893), in which a motive is repeated 840 times, taking over 18 hours. At the first full performance, which did not occur until 1963, only one audience member remained present through the entire event (Schonberg 1963).

Strategies for deliberate provocation follow known for-mulae. Certain artistic conceptions function as “audience trials” to see who can stand to remain. An exceptionally long, loud, noisy, quiet, or static piece tests the audience.

The line between provocation and free artistic expression is blurry, since what is considered provocative is context dependent, or more specifically culturally dependent. To some extent, provocation is in the eye of the beholder. For example, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (1913) was considered shocking at its Paris premiere but was celebrated as an artistic triumph in the same city a year later (Stravinsky 1936).

In some music, provocation occurs as a natural side-effect of a disparity between a composer’s unconventional vision and the conventional mindset of an audience. For example, the music of Varèse was long considered provocative by many critics and labeled as “a challenge to music as we know it.” The management of Philips went so far as to attempt to have Varèse’s Poème Électronique (1958) removed from the Philips Pavilion project (Trieb 1996). Similarly, Xenakis was a musical radical of an uncompromising nature. Many of his pieces, both electronic and instrumental, challenged accepted limits.

A tremendous furor was aroused in Paris in October 1968 at a performance of Bohor during the Xenakis Day at the city’s International Contemporary Music Week. By the end of the piece, some were affected by the high sound level to the point of screaming; others were standing and cheering. “Seventy percent of the people loved it and thirty percent hated it” estimated the composer from his own private sur-vey following the performance. (Brody 1971)

I recall being present at the Paris premiere of Xenakis’s composition S.709 (1994), a raw and obsessive electronic sonority that dared the audience to like it.

서술로서의 유머, 역설, 도발

유머와 역설, 도발로 서술적 문맥을 이끌 수 있다. 이들 모두 있어야 하는 것은 아니나-여러 심각한 작품들도 유머러스한 부분이 있다.

음악에서 유머의 심리는 무엇일까? 휴론(Huron 2006)은 이를 염려에 대한 반응으로서 다음과 같이 묘사한다:

음악가들이 웃음을 자아내는 소리를 창작할 때…나는 그들이 비관주의의 작용력을 빌리는 것이라 생각한다. 신속한 뇌의 작용은 언제나 뜻밖의 일을 나쁜 쪽으로 해석하려 한다. 뜻밖의 것을 수반하는 불확실함은 사람이 겁먹도록 만들기에 충분하다…그러나 이 두려움은 의식적으로 알아채지 못한 채 번개처럼 빠르게 나타났다 사라진다. 이 대응 반응을 잇따라 신속히 감정 반응이 나타나고, 중간적이거나 긍정적인 감정이 처음의 부정적인 반응을 재빨리 사라지게 한다… 결국, 음악이 이러한 강한 감정을 불러일으킬 때, 뇌는 그 상황이 받았을 첫 인상보다는 훨씬 낫다고 단순히 여기는 것이다.

휴론(Huron 2006)은 유머러스한 반응을 일으키기 위해 음악에서 사용되어 온 아홉 개의 장치를 엉뚱한, 복잡미묘한, 표류하는, 와해된, 믿기 어려운, 과도한, 모자란, 마땅치 않은, 잘못 인용한 소재들로 나열해 설명한다. 유머는 조소적인 것도 포함한다. 루크 페라리(Caux 2002에서 인용됨)는 말하길:

항시 진지하게 조소적인 것을 만드는 것이 내 작업의 상시 원칙이다. 나는 항상 합리적인 생각으로 보이는 어떤 것에서도 확실히 벗어나려 한다. 조롱은 내가 합리를 깨도록 한다: 누가 옳고, 누가 그른가? 이는 권력의 문제일 뿐이다.

페라리의 음악에서는 정색을 하고 부리는 유머가 늘 보이는데, 예를 들어 『짧은이야기』(2002)에서는 “누메로 콰투로(4번)?”를 쉴새없이 반복해 말하고, 『프롬나드 음악』(1969)에서는 경비대가 교대하는 장면에서 어처구니없는 소리들을 병치하며 이 장면에 대비시킨다.

음악 7.

루크 페라리의 『짧은이야기』(2002) 중 “누메로 콰투로” 발췌본.

찰스 닷지의 유쾌한 작품 『말노래』(1973)는 마크 스트랜드의 초현실적 시들을 컴퓨터가 노래한 것이 특징이다. 작곡가(Dodge 2000)는 주시하길:

나는 언제나 유머를 좋아했고 기이함과 비현실적인 것에 이끌렸다. 이 시들에 나타난 현재에 대한 발상들이 거의 꿈 같았다. 그래서인가 왠지 나를 매우 편안한 느낌이 들게 했다. 이런 비현실적인 주변 상황과 믿기지 않는 말들은 꽤 어울렸다. 그 말들은…만화같기도 하고 나를 즐겁게 했다.

닷지의 『닮은 것은 모두 우연이다』(1980)는 엔리코 카루소의 목소리를 유쾌하고도 비극적인 두 가지 효과로 마무리짓는다.

음악 8.

닷지의 『닮은 것은 모두 우연이다』(1980)의 발췌본.

장-장크 페리의 일렉트로닉 팝 음악에서는 과장된 유머의 느낌이 만연한데, 그의 『호박벌의 비행』(1975) 연주에서 실제 벌의 소리를 녹음한 것을 전치하여 사용한 것이 특징이다.

역설은 관계된 서술 전략으로서, 음악이 그 자신이나 주변 세상에 대해 비판하면서, 종종 유쾌한 효과를 준다. 어이없는 병치와 경음악의 인용, 과장 등이 그 예로, 여러 기법들로 역설을 전달한다. 역설은 제목이나 프로그램 노트를 통해 외적으로 전해지기도 한다. 스톡하우젠의 『피아노 소품』(CBS 32 21 0007)의 CBS 레코드 음반 1970 프로그램 노트가 한 예이다. 문서 형태를 가장하여, 작곡가는 녹음기간 중 피아니스트 알로이스 콘타르스키의 소비 습관을 포함하여, 주도면밀하게 녹음의 모든 양상을 상세히 적었다.

…[피아니스트는] 골수 콩소메 스프(전에 얘기했던 것보다는 훨씬 나은), 6 살팀보카 로마나, 상추로 식사를 하였다; 그는 ½리터의 요하니스베르크 리슬링 와인을 마셨다; 그 후 크레이트 쉬제트 케이크와 모카 커피 한 잔; 그는 몬테-크리스토 하바나 시가를 세 잔의 윌리엄스-페어브랜디와 함께 하며, 시가에 대한 유럽의 수입세에 대한 장황한 해설을 늘어 놓았고(무게에 근거한 세법을 이유로 스위스를 편들며), 하바나 시가의 준비와 포장에 대해서도 덧붙였다.

또 한 예로 존 케이지의 『변주IV』(1964)에서는 부조리적 역설이 나타난다. “몇 명의 연주자이든, 어떤 수단으로 만든 어떤 소리나 어떤 소리의 조합이든, 그 외에 다른 활동이 있든 없든.” 작품의 녹음은 따분한 라디오 방송의 발췌분들을 나열하여 다다이즘을 연상시키는 것들의 모음처럼 전개된다. 이들은 미국의 대중 문화를 비꼬는 하나의 논평을 만들어 낸다. 역설적인 리샘플링은 컷업(짜집기)나 플런더포닉스(섞어만들기)의 미학에 영향을 받은 예술가들이 반복해서 쓰는 주제이다 (Cutler 2000).

유머나 역설의 전략과 가깝게 연관된 것으로는 도발이 있다. 도발적인 작품은 청중을 팬과 적으로 나누는 경우가 많다. 헐버트 브륀(Brün 1985)이 말하길:

우리는 종종 연주회에 앉아서 음악을 들을 때 아직 그 곡을 “좋아하는” 관계는 아니지만 그것이 뒷줄에 앉은 사람들을 짜증나게 할 것임을 알아차리고는- 그 작품을 매우 편들게 된다. 나는 내 작품이 그처럼 단지 당신과 나 사이에 의혹을 불러일으킬 만한 수준에 있다고 제안하고자 한다. 그렇다, 이는 당신의 상상 속에서나 당신이 성내게 될 실제 상황에서 몇몇 사람들을 괴롭게 할 수 있고, 내가 이렇게 하는 것은 당신에 대한 나의 작은 호의이다.

두 측면으로 작용한 것에 주목하라: 어떤 사람은 타인이 짜증난 것을 알았기 때문에 최소한 부분적으로는 그 작품을 즐겼다. 어떤 예술가들은 일부러 도발시킨다; 그들은 청중을 놀라게 하고 싶다. 충격은 오래도록 써온 전략이다. 에릭 사티의 피아노를 위한 『벡사시옹』(1893)을 보자, 동기가 840번 반복되고, 18시간이 걸린다. 1963년이 되어서야 첫 완주가 이루어졌는데, 그 공연을 다 본 청중은 단 한 명이었다 (Schonberg 1963).

고의적인 도발을 위한 전략은 알려진 공식이 있다. 어떤 예술적 개념들은 누가 남아서 듣는지 보는 “청중 실험”으로 활용된다. 예외적으로 길거나, 크고, 시끄럽고, 조용하고, 정적인 작품은 청중을 시험에 들게 한다.

도발적인가의 여부는 문맥에 따라, 보다 정확하게는 문화적으로 차이가 있기 때문에, 도발과 자유로운 예술적 표현 사이의 경계는 불분명하다. 어느 정도는, 도발은 보는 자의 눈에 달려있다. 예를 들어, 스트라빈스키의 『봄의제전』(1913)은 파리 초연 시 충격적인 것으로 여겨졌지만 일년 후 같은 도시에서 예술적인 승리로 찬양되었다 (Stravinsky 1936).

어떤 작품에서는, 도발이 작곡가의 이례적인 기획과 청중의 관습적인 태도 사이의 격차에서 오는 자연스러운 부작용으로 나타난다. 예를 들어 바레즈의 음악은 오래도록 많은 비평에 의거하여 도발적으로 비쳐졌고 “우리가 알고 있는 음악에 대한 도전”이라는 꼬리표가 붙었다. 심지어 필립스 운영진이 필립스 파빌리온 프로젝트에서 바레즈의 『전자 시』(1958)를 빼버리려 한 적도 있었다(Trieb 1996). 유사하게, 크세나키스도 급진적인 음악가로서 강경한 성격을 가졌다. 그의 많은, 전자음향 작품과 기악 작품들 모두, 허용된 한계를 넘나든다.

1968년 10월 파리, 도시의 국제 현대 뮤직 위크 중 크세나키스의 날에 연주된 『보호르』는 엄청나게 격렬한 반응을 불러일으켰다. 작품이 끝날 무렵, 몇몇 사람들은 소리를 지를만큼 높은 소리 강도에 시달렸고; 다른 이들은 서서 환호를 질렀다. 작곡가는 연주회 이후 자신의 개인적인 조사로 추정하길 “사람들 중 70퍼센트는 좋아했고 30 퍼센트는 싫어했다” (Brody 1971).

내가 크세나키스의 작품 『S.709』 (1994)의 파리 초연에 참석했을때를 떠올려보면, 과감하게 청중들이 좋아할 것을 무릅쓴 것 같은, 날 것 그대로를 집요하게 사용한 전자 음향이 울려퍼졌다.

Narrative Repose

Compositional processes need a balance between sparsity, relaxation, and repose as well as density, tension, and action. As in the cinema, slowing down the action and allowing the direction to meander provides an opportunity to build up suspense–underlying tension. As Herbert Brün (1984) observed:

Boredom is a compositional parameter.

Composers sometimes deliberately insert sections that stall or freeze the narrative, as a preparation for intense fireworks to come. Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) comes to mind, with its sparse and frozen middle section between 3:17 and 8:50 preceding a colorful finale (8:51-13:15).

Likewise, the long reposing phrases that characterize the style of Ludger Brümmer induce a sense of expectation for brief dramatic flourishes, as in works such as The gates of H (1993), CRI (1995), La cloche sans vallées (1998), and Glassharfe (2006).

서술적 휴식

작곡 과정에서는 밀도와 긴장, 움직임뿐 아니라 희소와 완화, 휴식 간의 균형도 필요하다. 영화에서처럼, 동작의 속도를 늦추고 방향을 이리저리 비틂으로써 근원적인 긴장감-서스펜스를 구축하는 기회를 잡을 수 있다. 허버트 브륀(Brün 1984)이 말하길:

지루함은 작곡의 매개 변수가 된다.

작곡가는 때때로 강렬한 폭죽을 터뜨리기 위한 준비장치로, 서술의 흐름을 지연하거나 정지시키는 부분을 의도적으로 끼워넣는다. 스톡하우젠 『소년의 노래』(1956)가 떠오르는데, 8:51부터 13:15 까지 파란만장한 피날레에 앞서 3:17과 8:50 사이 성기고 멎은 듯한 중간 부분이 있다.

이런 방식의, 긴 휴식 구절은 르트거 브뤼머가 주요하게 쓰는 스타일인데, 그의 『게이트H』(1993), 『시알아이』(1995), 『밸리없는 종』(1988), 『유리하프』(2006)와 같은 작품에서 드라마틱한 사건이 펼쳐질 것 같은 기대감을 유도한다.

Conclusion: Hearing Narrative Structure

A composer can design narrative structure, but will listeners hear it? Part of the pleasure of listening to music is decoding the syntactic structure as it unfolds. A clear and simple narrative design is decipherable to most listeners. If a listener cannot hear any patterns or organization in a piece of music they will likely dismiss it as boring chaos.

At the same time, in a piece of new electronic music of sufficient complexity, it is unlikely that a listener will hear every detail that the composer designs. Like any crafts-person, composers of all stripes embroider patterns for their own amusement without expectation that audiences will decipher them. A communication model of music–in which the composer transmits a message that is received and unambiguously decoded by listeners–is not realistic. “Imperfect” communication, in which the message perceived by each listener is unique, is part of the fascination of music.

Even if a listener was able to somehow perfectly track the narrative structure–to parse the syntax on all time scales–this does not account for the ineffable factor of taste in listening. Just because I understand how a work is organized does not mean that I will like it. Inversely, I do not need to understand how a work is constructed in order to marvel at it. As in all other aspects of life, there is no accounting for taste; the appreciation of beauty is subjective; nothing has universal appeal.

Recent research shows that our brains experience music not only as emotional stimulus but also as an analog of active physical motion (Echoes 2011). In effect, the composer sails the listener on a fantastic voyage. Let each person make up their own mind about what they experience.

결론: 서술 구조 듣기

작곡가는 서술 구조를 계획하여 만들지만, 청자들이 이를 알아들을까? 음악이 전개하는 데 따라 그 구문론적 구조를 해석해나가는 것은 음악을 듣는 즐거움 중 한 부분이다. 명료하고 간단한 서술 계획은 대부분의 청중들이 해석할 수 있다. 청자가 음악작품 속 어떤 패턴이나 짜임새를 놓치게 되면 그것들은 아마 따분한 혼란 정도로 넘겨질 것이다.

그와 동시에, 꽤 복잡한 새로운 전자음악 작품에서, 작곡가가 기획한 모든 사항들을 청자가 상세히 알아듣기는 어려울 것이다. 여느 장인들처럼, 온갖 계층의 작곡가들은 청중들의 이해를 기대함 없이 그들 자신의 유희를 위해 도안을 윤색한다. 작곡가가 메시지를 전달하면 청자가 이를 받아 명백하게 해석한다는- 음악의 소통 모델은 비현실적이다. 각 청자가 받아들이는 메시지는 개별적이라는 “불완전” 소통이 음악의 매혹스러운 점 중 하나이다.

청자가 어느정도 완벽하게 서술 구조를 따라 -모든 시간차원에서 구문들을 해석할 수 있다 하더라도- 이것이 음악을 감상할 때 취향이라는 형언할 수 없는 인자까지 해명하는 것은 아니다. 내가 어떤 작품이 어떻게 구성되었는지 안다는 것이 그 작품을 좋아한다는 의미는 아니기 때문이다. 역으로, 나는 어떤 작품에 감탄하는 데 그 곡이 어떻게 만들어졌는지 이해하는 것은 필요치 않다. 삶의 모든 다른 면에서처럼, 기호도 제각각이다; 아름다움을 느끼는 것은 주관적이다; 모두 다에게 매력적인 것이란 없다.

최근 연구는 우리의 뇌가 음악을 들을 때 감정적인 자극과 더불어 활동적인 신체 운동을 하는 것과 유사한 경험을 한다고 한다 (Echoes 2011). 결국, 작곡가는 청중을 항해하며 환상적인 여행을 하는 것이다. 각각 그들이 경험한 것에 대해 각자 나름의 생각을 하도록 두라.

References

Berry, W. (1987). Structural Functions in Music. New York: Dover.

Bodin, L. G. (2004). “Music–an artform without borders?” Unpublished manuscript.

Brody, J. (1971). Program notes to Iannis Xenakis: Electroacoustic Music. Nonesuch Records H-71246.

Brown, E. (1967). “Form in new music.” Music of the Avant-Garde 1/1: 48-51. (Reprinted in Music of the Avant-Garde: 24-34. Austin, L. / Kahn, D. [eds.] (2011). Berkeley: University of California Press).

Brün, H. (1984). Personal communication.

Brün, H. (1985). “Interview with Herbert Brün.” [Quoted in Composers and the Computer: 10. Hamlin, P. / Roads, C. [Eds.] (1985). Madison, Wisconsin: A-R Editions.]

Caux, J. (2002). Presque rien avec Luc Ferrari. Paris: Éditions Main’Oeuvre. [Translated by Hansen, J. Almost Nothing with Luc Ferrari. (2012). Los Angeles: Errant Bodies Press.]

Clarke, E. (2011). “Music perception and musical consciousness.” In Music and Consciousness: Psychological and Cultural Perspectives: 193-213. Clarke, D. / Clarke, E. [Eds.] Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cutler, C. (2000). “Plunderphonics” In Music, Electronic Media and Culture: 87-114. Emmerson, S. [Ed.] Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishers.

Echoes. (2011). “Acoustics in the News.” Echoes: Acoustical Society of America Newsletter 21/3: 8.

Gayou, E. (2002). “Mots de l’immédiat, entretien de Bernard Parmegiani avec Elisabeth Gayou.” In Bernard Parmegiani: Portraits Polychrome: 17-38. Gayou, E. [Ed.] Paris: CDMC, INA-GRM.

Godard, J. L. (1966). Quoted in the commentary to Masculin-Feminin. DVD. New York: Criterion Collection.

Hoffman, E. (2012). “Itunes: multiple subjectivities and narrative method in computer music.” Computer Music Journal 36/4: 40-58.

Huron, D. (2006). Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Lerdahl, F. (1988). “Cognitive constraints on compositional systems.” In Generative Processes in Music: The Psychology of Performance, Improvisation, and Composition: 231-259. Sloboda, J. [Ed.] Oxford: Oxford University Press.

참고자료

Meyer, L. (1956). Emotion and Meaning in Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nattiez, J. J. (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music. Carolyn Abbate, translator. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Risset, J. C. (2004). “The liberation of sound, artscience and the digital domain: contacts with Edgard Varèse.” Contemporary Music Review 23/2: 27-54.

Roads, C. (2004). “The path to Half-life.” POINT LINE CLOUD. DVD. ASP 3000. San Francisco: Asphodel. Retrieved from www.curtisroads.org/articles.

Roads, C. (2015). Composing Electronic Music: A New Aesthetic. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schonberg, H. (1963). “A Long, Long Night (and Day) at the Piano; Satie's ‘Vexations’ Played 840 Times by Relay Team.” The New York Times on 11 September 1963: 45.

Smalley, D. (1986). “Spectromorphology and structuring processes.” In The Language of Electroacoustic Music. Emmerson, S. [Ed.] New York:

Harwood Academic Publishers.

Smalley, D. (1997). “Spectromorphology: explaining sound shapes.” Organised Sound 2/2: 107-126.

Stockhausen, K. (1972). Four Criteria of Electronic Music with Examples from Kontakte. Film of lecture at Oxford University. Kürten:

Stockhausen Verlag. [See also Maconie (1989), which contains the edited text of this lecture.]

Stravinsky, I. (1936). Stravinsky: An Autobiography. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Terry, C. S. (1963). The Music of Bach: An Introduction. New York: Dover Publications.

Thompson, D. (1942). On Growth and Form. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trieb, M. (1996). Space Calculated in Seconds: The Philips Pavilion, Le Corbusier, Edgard Varèse. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Vivier, C. (1985). Quoted in “Hommage à Claude Vivier 1948-1983.” Almeida International Festival of Contemporary Music and Performance. June 8-July 8, 1985, Islington, London. Retrieved from oques.at.ua/news/claude_vivier_klod_vive_works/2010-06-21-28.

논문투고일: 2019년 11월8일

논문심사일: 2019년 12월2일

게재확정일: 2019년 12월6일