Translanguaging in Mexican Electronic Music Instrument Designers

Pablo Dodero

University of California, San Diego, United States

pdoder [at] ucsd.edu

Abstract

The technical language surrounding electronic music instruments is continually expanding with their increased popularity and use. The field’s prioritization of English, the most commonly used language among manufacturers, presents a language barrier for non-native English speakers. New generations of independent electronic music instrument developers in countries like Mexico utilize a mix of English and Spanish to label and describe the features and functions of their products. This is due to a lack of terminology in Spanish coupled with a desire to compete in the global market. My paper highlights current examples in which Mexican builders like Paradox Effects engage with English and are actively searching for creative ways to enrich audio jargon in Spanish. Using objects or artifacts as hermeneutic, I delineate a methodology that considers perspectives from fields like critical linguistics and science and technology studies (STS) to highlight the role English plays in creativity and sonic imaginaries for the non-fluent.

Keywords

electronic music instruments, translanguaging, sonic imaginaries.

멕시코 전자음악 악기 디자이너들의 다언어 사용

파블로 도데로캘리포니아대학교, 샌디에고, 미국

pdoder [at] ucsd.edu

초록

전자 악기를 둘어싼 기술적 용어는 그 인기와 사용도 증가에 따라 지속적으로 확장되고 있다. 제조업체들이 가장 흔히 사용하는 언어로서, 영어에 대한 현장 선호도로 인해 비영어권 사람들에게 언어 장벽이 존재한다. 멕시코 같은 나라들의 독립적인 신세대 전자악기 개발자들은 영어와 스페인어를 혼용하여 제품의 특징과 기능을 이름짓고 설명한다. 이는 스페인어의 용어 부족과 글로벌 시장에서 경쟁력을 높이려는 바람이 혼재한 데 기인한다. 이 논문은 패러독스 이펙츠Paradox Effects같은 멕시코 제작자들이 영어를 활용하되 적극적으로 스페인식 오디오 용어를 만들고 늘리기 위한 연구를 하는 현재의 사례들을 집중조명한다. 저자는 해석학적으로 사물이나 가공물을 사용하며, 영어가 유창하지 않은 사람들에게 창의성이나 음향적 상상력을 줄 수 있도록 비판적 언어학이나 과학기술연구 같은 분야의 시각을 고려한 방법론에 대하여 묘사한다.

주제어

전자 악기, 다언어 사용, 소리 이미지.

I FELT… That the book I shall write will be neither in English nor in Latin; and this for the one reason…namely, that the language in which it may be given me not only to write, but also to think, will not be Latin, or English, or Italian, or Spanish, but a language in which dumb things speak to me, and in which, it may be, I shall at last have to respond in my grave to an Unknown Judge. (Hugo Von Hofmannsthal. The Letter of Lord Chandos 1902)

I first became interested in the way electronic music instruments (EMIs) are designed and marketed working at a small music store in the town of San Ysidro which is the southernmost city in California bordering Mexico. Our clientele consisted mainly of musicians and students from Mexico and the U.S., and our interactions were predominantly in Spanish. However, when it came down to discussing electronic music equipment, the use of English was unavoidable. Although it is fairly common to switch between English and Spanish in a border region like San Ysidro and Tijuana, one thing that remains consistent is when it comes to EMI’s, Spanish speakers must adapt to English due to a lack of terminology in labels, manuals, and marketing material in their native tongue. In recent years companies in Mexico like Paradox Effects are engaging with English in ways that illustrate what linguistics scholars refer to as translanguaging. While early scholarship regarding the term is rooted in pedagogy, more recent work in critical and applied linguistics has shown how it can be adapted into a practical theory. My aim is to enlist these practical approaches to reading labels–the actual text printed on the surface of the EMI– and marketing materials of two EMIs designed and manufactured in Mexico to illustrate the tensions between English and Spanish that happen at the interface level. Because language does not affect the functionality of an EMI, I bring into conversation scholarly work from the field of science and technology studies (STS) to parse out the role English plays in both mediation and commercialization, as well as its potential stifling effects on what James Mooney and Trevor Pinch refer to as sonic imaginaries.

Electronic Music Instruments

There exists a lack of consistency with regards to what is considered an EMI. The list may cover anything from a transistor-based guitar pedal to a complex sequencer that uses MIDI and a microprocessor. Controllers do not make a sound, but mediate between a user and music software. Recording devices record and reproduce sound, and are sometimes treated as instruments. From a legal stand-point, U.S. agencies like the FCC regulate equipment under Title 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations and categorize based on specific concerns regarding their components. The task of taxonomizing EMIs is beyond the scope of this paper, and for the purposes of this discussion, I consider an EMI any electronic device designed for the musician or performer. However, it is helpful to consider the aforementioned perspectives alongside some of the ways in which scholarly work has discussed EMI’s from a technological standpoint.

Bert Bongers provides a useful birds-eye view of the evolution in technology surrounding musical instruments from objects (drums, cymbals) to passive mechanical systems (saxophones, violins) to electric (electric guitars) to the present-day instruments that “are combinations of (successive) technologies” (Bongers 2007: 10). EMIs offer new possibilities for music making and expression, improve workflow and accessibility, and by consequence increase the potential for new users to adopt them. A chronological trace of innovation provides scholars ways to study, unearth, or critically engage with the effects of technology on music-making and sound-recording technology, as is the case of tape music, musique concrete, or sampling. The breadth of academic inquiry has grown exponentially with regards to EMIs. Recent scholarly work surrounding emerging music technology is concerned with the impact they have had on performance and improvisation (Butler 2014), the motivations and desired outcomes when designing new instruments (Emerson/ Eggerman 2018), or the influence on the piano keyboard on interface design (Dolan 2012). The focus of this paper is to bring into light an aspect of design that has evolved into fixity: English is the lingua franca of design and marketing of EMIs. It is the aim of this paper to illustrate how language becomes a shaping force in EMI’s and by casting a critical lens on language practices interesting questions surrounding agency, mediation, and imagination emerge.

Interface and Labels

EMI labels, marketing materials, and manuals are meant to show what an instrument was intended to be used for. Many users spend time with images or copies of manuals before they are able to physically own an instrument. The words on the interface will usually point to a function, range, or signal flow of the instrument and describe its “affordances” (Gibson 1977, as cited in Butler 2017). The labels and instruction manuals are then an extension of what is often referred to as the “interface.” In Playing Something that Runs, Mark J. Butler discusses the term interface as a type of EMI largely concerned with mediation between a performer and a technology, but extends the definition stating it “denotes something more than simply the mediating technology; in particular, it refers to the actual site of mediation: the surface of the mixing board and sliders, or the graphical representation on the screen of the computer” (2017). Butler’s definition of interface is useful because it illustrates mediation in a way that includes the visual layout of an EMI not just in terms of functionality or at the “macroperception” level (Verbeek 2017). Butler is concerned with the physical design of the instruments and affordances they provide to performers and improvisers. This, however, implies a familiarity with the instrument after spending time working with it. By looking at the practices of two Mexican EMI companies, I problematize the idea of mediation and performance to include language as part of the schema.

Translanguaging Practice Theory

The term “translanguaging” has its origins in linguistics work concerned with bilingual education. Li Wei states it was “not originally intended as a theoretical concept, but a descriptive label for a specific language practice” (Wei 2017: 15). A definition of “translanguaging” that is helpful to frame this paper is as “the language practices of bilinguals not as two autonomous language systems as has been traditionally the case, but as one linguistic repertoire with features that have been societally constructed as belonging to two separate languages” (García Wei 2108: 2). In Translanguaging as a Practical Theory, Li presents a way in which the term can be extended into a practical approach to language practices beyond the classroom. Another important feature of Wei’s approach is that it is meant “not to offer predictions or solutions but interpretations that can be used to observe, interpret, and understand other practices and phenomena” (11). I agree with this method because my intention with interpreting the language practices in my case studies is not to speculate on the future practices of Mexican designers or present the pervasiveness of English as a problem, but rather activate a new line of inquiry that pertains to agency and technological innovation.

Materiality of Language

The spread of English across the world has often been studied as a result of globalization, cultural hegemony, and a homogenization of culture. My aim is not to delve deep into the causes and effects of this phenomenon, but to enlist the word of critical linguistics to illustrate the localized ways in which English is employed by two EMIs designed by Mexican companies who design, build, and market their products in Mexico to the rest of the world. To clarify, my first case study, Paradox Effects and their guitar pedal Fuzz E Cat, is located in Tijuana, Mexico, within the border region; and my second case study is Bocuma Synths, located in Guadalajara, Mexico, 2,200km south of the border. Although it would be a monumental task to describe the different relationships both companies have to English from a geographical and cultural standpoint, it could provide insight into the differences and similarities in their translanguaging practices.

Another important reason why I chose a translanguaging practice theory as a method is because it allows me to cast my peers and interlocutors within a more robust framework of agency. I argue that having a single language to learn, discuss, create, and ontologize sonic phenomena stifles creativity. In Decolonising the Mind, Ngũgĩ Wa Thiong'o argues that “language, any language, has a dual character: it is a means of communication and a carrier of culture” (Thiong’o 1986: 13). This does not mean, however, that companies are unable to reappropriate the English language to make new instruments representative of their vision. The scope of this paper does not explore the relationship language has to sonic phenomena, as it is part of a future dissertation work. By bringing translanguaging into the study of EMIs I illustrate how language plays a central role in interface design and mediation. It is worth mentioning that I employ my own position-as-method as a member of the community that I am researching. Therefore my interpretation is both from within the locality and from a theorized perspective.

Case Study 1: Paradox Effects

To compete in global markets, many products are labeled in English, not just musical instruments. This ebb and flow of global vs. local practices requires more complexity in our thinking of language practices. Linguistic scholar Alastair Pennycook, an important figure in the study of global Englishes, states that

The multidimensional nature of both dominating modes of globalization - corporatization, capitalization, conceptualization - and of resistant and localizing modes - transcul-turation, translocalization, transformation - lead to very different linguistic and cultural practices than international domination or national localization. It is a far more dynamic space of flows.

According to Pennycook, an effective theorization of linguistic practices along the axes of global vs. local must encompass a definition that allows for more than one form of globalization. One such case is the manner in which Mexico has become a site of outsourcing manufacturing processes for transnational companies.

Efrén Castro, one of the co-founders of Paradox Effects, studied Electronic Engineering at Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. His growing interests in effect pedals began to clash with the school’s focus on the job market. The effects of globalization extend to universities' curricula due to the growing demand for engineers in maquiladoras. In theory, a career in electronic engineering offers a range of possibilities for the graduate, but in practice most roads lead to working for a transnational company in one of their factories. During his time at UABC, Castro, who is also a musician, learned about electronic circuits. He began to tinker with a circuit that is commonly adopted in DIY circles, the fuzz pedal.

In a box sitting in my studio I keep guitar pedals that I obtained when my main instrument was the electric guitar and bass. It doesn’t get much use lately because I shifted my musical practice to synthesizers, but I keep it as part of my collection because it is one the first effect pedals designed, manufactured, and marketed in Tijuana, Mexico by Paradox Effects. The Fuzz-e Cat, as it is called, is “a roaring oscillatory feline, a highly sensitive Fuzz that creates many textures with few controls” (Paradox Effects 2017: para. 1). Although the marketing materials are all in English, the faceplate looks like an electrified cartoon cat with two knobs for eyes which is labeled in Spanish and English. As shown in Figure 1, the left knob is labeled “Volúmen” and the right one “Fuzz” (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fuzz-E Cat effect pedal. Fuzz-E Cat front panel From https://paradoxeffects.com/products/fuzz-e-cat [digital image]

Sound 1.

Paradox Effects Fuzz E Cat 100% Oscillation.

In the same manner that the pedal’s zoomorphic design layout only contributes to the aesthetic quality of the pedal, I argue that the use of the word “Volúmen” is a symbolic gesture signaling the nationality and identity of the company. However, at the time of release, Paradox marketed their pedals in English. Having a somewhat strong social media presence, the company posts videos on YouTube, Instagram, and Tik-Tok in Spanish, some of them with English subtitles.

Paradox markets the Fuzz-e Cat as “a silicon based effect, our amorphous take on the Fuzz Face topology” (Paradox Effects 2017: para. 1). The Fuzz Face mentioned in their blurb is a highly regarded effect pedal designed in 1966 by Arbiter Electronics Ltd. and made famous by artists like Jimmy Hendrix. Its circuitry has been reimagined by many effect pedal designers from across the globe due to the ease with which it can be built and modified. But by en-gaging with the Fuzz Face circuit in their product line, Paradox is performing a translocal practice. In other words, by signaling the topology of the famous Fuzz Face as the inspiration for the Fuzz-e Cat, Paradox is staking its claim in a global exchange of ideas surrounding pedal design that extends beyond their locality. The term amor-phous may then extend not only to the arrangement of components in the circuit, but also the combination of languages on the label. By looking at Paradox’s own take on the Fuzz Face circuit we engage in “cross-cultural stud-ies of the use of electronic music technology and instru-ments” (Bakan et al. 1990).

Here, language and material are imbricated. Symbolic language becomes concrete the moment circuit boards are printed and enclosures are painted. While critical linguistics accounts for the usage of English in localities, many times spoken, codified, and appropriated, the practice I am interested in is materialized in metal, paint, printed, and online text. During this process of materiali-zation is when I consider English to become part of the interface of the instrument. Peter Paul Verbeek, a sci-ence and technology studies scholar, employs the term material hermeneutics as a framework for studying rela-tionships between humans and technological objects. Verbeek derives this term from the ideas of Don Ihde, specifically hermeneutic relations. Hermeneutic relations describe how humans and technological artifacts engage with each other. Material Hermeneutics allows for a more robust schema or network in the Latourian sense, to dif-ferentiate more inclusive elements of technological me-diation as actants. I consider this study to be in line with Actor-Network Theory as I unpack and reconfigure ideas commonly taken as given in the study of EMIs. The con-cept of interface or the concept of accessibility require reassessment the moment the pervasiveness of English comes into play.

Returning to the use of the term amorphous, a word used to describe something shapeless or with no clearly defined boundaries, I interpret this as a necessary descriptive act that allows ambivalence for an act that has little precedent in the global market of effect pedals: marketing from a country whose national identity does not read as technologically proficient.

Translanguaging and Translation

In 2021, five years after the Fuzz-e Cat, Paradox released a pedal called Carmesí. The pedal is an all-pass phase modulator, a more complex circuit than a fuzz pedal, usually requiring more functions and knobs. The Carmesí’s interface consists of six variable knobs and two switches all labeled in Spanish. One of the buttons, “sendero,” enables an envelope follower processed by a sample and hold function. This feature of the pedal essentially traces the path of the signal that comes in and creates a new one based on conditional functions afforded by the cir-cuit. The word “sendero” means path and it is most com-monly used to describe a hiking trail or a route rather than a single path in electronics. In the context of the Carmesí, it is a pedal that has been highly conceptualized both in function and design.

On the Paradox Effects website, they include the follow-ing tagline: “IN THE HYPNOTIC DESERT, A CRIMSON EYE AWAITS, They say that in the hypnotic desert, between the hot sand and delirium, you can find a crimson eye that hides a mystery” (Paradox Effects 2021).

Figure 2.

Carmesí front panel. Paradox Effects from https://paradoxeffects.com/products/carmesi

Sound 2.

Paradox Effects Carmesí - Ascending Square Phasing.

As an EMI, Carmesí is an effect pedal that allows the user to sculpt sound by running an audio signal through its circuit, but by using creative and imaginary narratives, they enlist what James Mooney and Trevor Pinch de-scribed as a “sonic imaginary” in the article “Sonic Imaginaries: How Hugh Davies and David Van Koevering Performed Electronic Music’s Future” (Mooney/ Pinch 2021). Their definition of sonic imaginaries presents it as “a way of imagining and bringing forth a shared sonic world or experience grounded in technology, institutions, and networks'' (2021). I argue that the term “sendero,” which is both unconventional for labeling an electronic device and foreign to the effect pedal market, prioritized the sonic imaginary of Carmesí, rather than its technological affordances.

From the time that Paradox began to market their guitar pedals locally in Tijuana to now having distribution in various international markets and counting professional musicians as users, the company’s slogan has shifted to “Un Lenguaje Sónico,” or a sonic language. In one of our conversations Castro commented, “Yes we make overdrives, fuzzes, and whatnot, but we are working with technological tools to be creative” (E. Castro personal communica-tion. January 2021). This is an important distinction that shows how creativity has become an important marker for Paradox Effects in the global marketplace. Paradox now labels their devices in Spanish, but continues to mar-ket on their website in English. I argue that this deliberate combination of both languages for very specific purposes sheds light on the fluidity of globalization. Language print-ed on the label’s interface does not affect its functionality, but shapes its interface. On the other hand, in marketing materials English continues to take precedent in the glob-al marketplace.

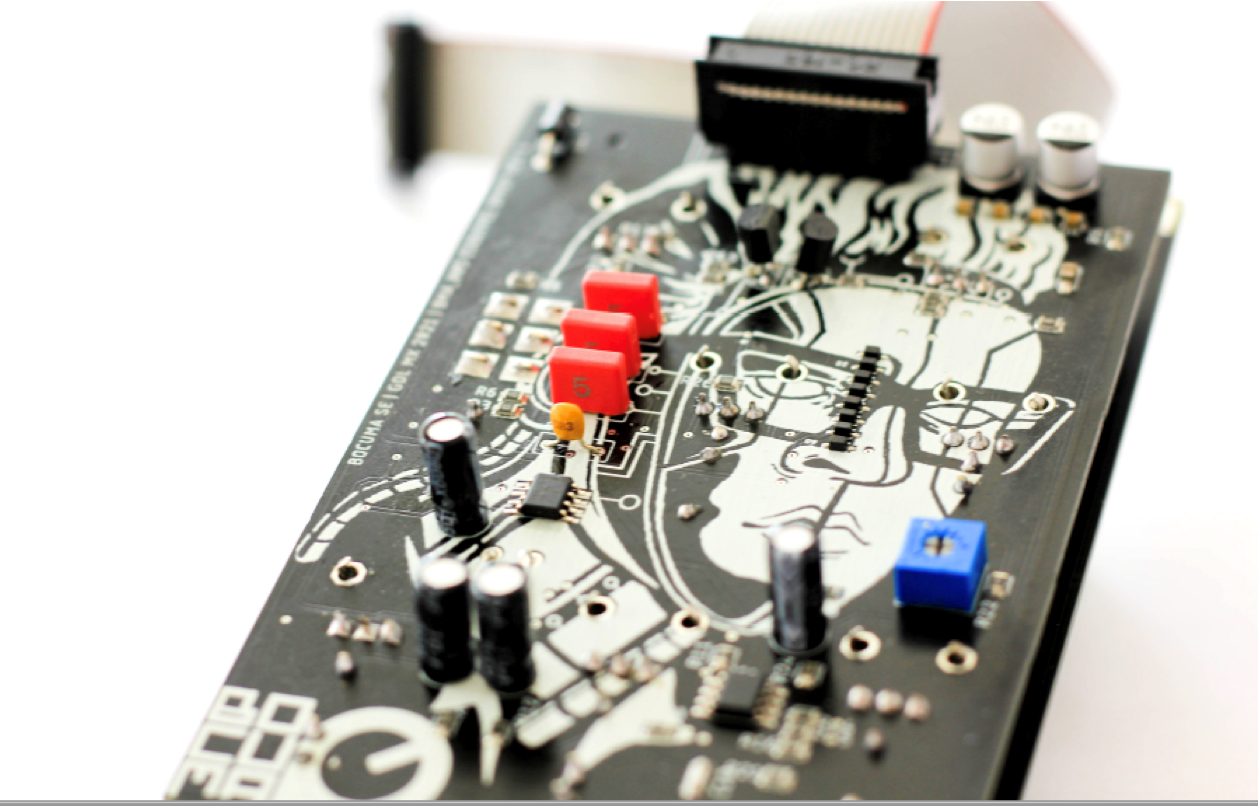

Case Study 2: Bocuma

Bocuma is a synthesizer company from Guadalajara, Mexico founded by Emmanuel Galvan. I was made aware of their existence through an exhibition of Mexican musical technology organized by Paradox Effects in Tijuana in 2021. Galván's background is also in electronic engineer-ing, and like Castro, it was easy for him to work with EMI circuits. Bocuma’s website currently offers a build-your-own kit for a pocket-sized synthesizer and its flagship product, the Esquivel, a state variable filter built in Euro-rack format for modular synthesizer systems.

The Esquivel is a well-constructed state variable filter module with a very minimal and clean design. Eurorack format is substantially smaller and does not lend itself for larger fonts or illustrations like a guitar pedal. Bocuma has released two different versions of the Esquivel filter and looking specifically at the labels of both versions, V1 and V2, we find that there was a change in the language of one of the functions. In V1 the cutoff frequency knob was originally labeled with the word “cutoff” and in V2 it now shows a pictogram of a small graph illustrating the cutoff frequency.

Figure 3.

Bocuma “Esquivel” State-Variable Filter Module Esquivel Front Panels. Esquivel faceplates V1 and V2. Bocuma. www.bocuma.mx/product/esquivel

Sound 3.

Bocuma Filter Sweep Example.

During an interview I conducted with Galvan I asked him about Bocuma’s decision to change the label. He responded: “I never considered language as part of the design process, but coincidentally I have been shifting to symbols or abbreviations of words to avoid using strictly English in my designs” (E. Galvan personal communication. February 4th, 2021). While Galvan does not take issue with using English when necessary, English on the label creates some tension. In this sense, the translanguaging act becomes a gradual process and the pictogram provides a neutral language that avoids the task of translating into Spanish, creating a new term, and educating their potential customers on its meaning. The manner in which the pictogram reads as neutral to Galvan, in the same manner that English did due to its pervasiveness in the global market, brings up questions of whether English has any other functional use beyond a common language to communicate in.

The filter takes its name from Mexican space-age pop composer and innovator Juan García Esquivel. His musical legacy in the genres of exotica, lounge, and space-age pop have made him into a national hero in Mexico and the rest of the world. While he may not be as well-known with younger generations, for Galvan, he is a role model. Galvan stated that he draws inspiration from the compos-er not just because of his body of work, but also because he studied engineering. He then imagined how Esquivel’s own engineering background may have contributed to his innovative approach to composing and recording using synthesizers. In our conversation Galvan mentioned that he was inspired to design a functional state-variable filter for performers and studio musicians, but inspired by the legacy of Esquivel. Eurorack modules are usually purchased separately and part of the reason to adopt this format is because they are modular, meaning that they can be used with other modules of the same format. On the reverse side of Esquivel's printed circuit board, Bocuma decided to print an illustration of Esquivel’s face.

Figure 4.

Esquivel illustration printed on circuit board. Esquivel module back panel. Bocuma. www.bocuma.mx/product/esquivelEsquivel illustration printed on circuit board. Esquivel module back panel. Bocuma. www.bocuma.mx/product/esquivel

Sound 4.

Juan García Esquivel - Latin-Esque.

Because the filter is not tied to any particular method or technique used by Esquivel, I argue that the filter pays homage to an imagined or speculative narrative surrounding the composer. In similar fashion to how Ytasha Womack defines Afrofuturism as “an intersection of imag-ination, technology, the future, and liberation” (2013: 9), Bocuma’s filter reimagines Esquivel’s legacy through technology, visual art, and fiction. Printing his image in the back of the module becomes a symbolic gesture regard-ing the influence and presence of Esquivel in the design process. Because Bocuma is part of a new generation of EMI companies, by signaling Esquivel’s exceptional career, the filter activates the epistemology of Mexican musical and technological innovation.

Conclusions

For the last few years, the maker community in Mexico has begun to build stronger platforms for collaboration. Inspired by the DIY ethos of the global English-speaking communities centered on EMIs, Mexican designers, educators, and musicians have shifted the conversation to Spanish or a blend of English and Spanish, and in some cases pictograms. Social media accounts like Eurorack en Español have emerged, offering tutorials in Spanish and working with synthesizer companies in the U.S. to translate manuals and technical sheets. Paradox has currently labeled all of their products in Spanish or abbreviated English and has changed their slogan to “Un Lenguaje Sónico,” a sonic language, shifting from a functional forward design practice to one that allows sonic imaginaries to contribute to the ideation process. Paradox also organized the Exhibición de Tecnología Musical Mexicana (Mexican Musical Technology Exhibition) to encourage collaboration and dialogue among other national makers.

I argue that by performing close reads on EMIs, treating them as complex and robust networks of mediation and agency, we are able to parse out the ways in which language carries cultural hegemony that becomes consolidated into the material. Translanguaging offers us a unique perspective into the subjectivities of bilingual musicians and EMI designers, as well as the fluidity of global flows of information. By casting EMIs in a network that affords language agency within the interface and as a force that shapes imagination and marketability, it allows translanguaging acts the ability to become a site of knowledge rather than a consequence of globalization. Finally I’d like to cite Nick Millevoi’s review of the Carmesí in the guitar magazine Premier Guitar, which I argue illustrates the othering effects of language to the non-fluent, when engaging with a piece of technology:

Paradox Effects are a Tijuana-based company whose pedals usually offer a tweaked take on traditional effects. Before I could dig into this pedal, I headed over to the Paradox site to translate the control names, which are in Spanish, before I could wrap my head around the controls. (Millevoi 2021)

References

Bakan, M. B. et al. (1990). Demystifying and classifying electronic music instruments. Selected reports in ethnomusicology volume viii: issues in organology 8: 37–64. University of California Los Angeles.

Bongers, B. (2007). Electronic musical instruments: Experiences of a new luthier. Leonardo Music Journal : 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1162/lmj.2007.17.9

Butler, M. J. (2018) Experimentalisms in practice: Music perspectives from Latin America. Oxford University Press.

Code of Federal Regulations. Title 47. §15.3.

Dolan, E. I. (2012). Toward a musicology of interfaces. Keyboard Perspectives V: Yearbook of the Westfield Center for Historical Keyboard Studies. Westfield Center. 1-12.

Emerson, G./ Egermann, H. (2018). Exploring the motivations for building new digital musical instruments. Musicae Scientiae 24/3: 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1029864918802983

García, O./ Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Millevoi, N. (2021, July 15). Paradox Effects Carmesí Review. Premier Guitar. https://www.premierguitar.com/ gear/reviews/paradox-effects-carmesi

Mooney, J./ Pinch, T. (2021). How Hugh Davies and David Van Koevering performed electronic music’s future. In Rethinking Music Through Science and Technology Studies: 113-149. Routledge.

Pennycook, A. (2008). Global englishes and transcultural flows. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203088807

Thiong’O, W. N. (1986). Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. James Currey.

Verbeek, P. (2005). What things do: Philosophical reflections on technology, agency, and design. Penn State UP.

Wei, L. (2017). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics 39/2: 261–261. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx044

Womack, Y. (2013). Afrofuturism: The world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture. Lawrence Hill Books.

논문투고일: 2022년 10월01일

논문심사일: 2022년 11월22일

게재확정일: 2022년 12월15일